Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

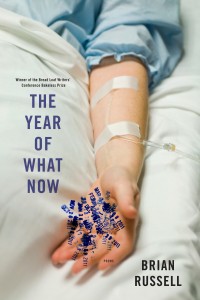

The Year of What Now, Graywolf Press, 2013

Synopsis: After a woman falls suddenly ill, doctors struggle to discover what’s wrong with her, while her husband confronts the unimaginable possibility of life without her.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

I suppose it comes down to intent. Am I setting out to write a book or am I writing a completely random assortment of poems that in no way speak to one another and have no common themes, interests, etc. until I realize that I have at least 48 pages of these unique snowflakes and proudly declare, well I’ll be! I’ve written a book! I think what we call project books are simply books whose structural framework is more immediately visible. It’s hard for me to imagine what kind of book is not a project of some kind, whether consciously or subconsciously.

Furthermore! I’d say the random-assortment-of-poem approach to bookmaking is completely obsolete. As more and more poems are published on the worldwide web and freely available for me to read whenever I’d like, a book, as a self-contained object that I have to pay for and exert effort to acquire, must do something more, must be more than the sum of its parts. If a book takes on average two years (from beginning of self-editing to publish date) to produce, it must be better than what Google can produce in one second. While a beautiful cover and nice paper and a strong binding are all desirable features of a book, they alone do not make a book a book.

So, did I intend to write a book? I did. Though, as I was writing, I never thought of it in terms of a project but rather I had a kind of story I needed to tell and I believe that poetry is able to tell a story in a particular way with particular freedoms and opportunities for surprise that no other art form offers. What makes my book a project is its narrative through-line, but the narrative here is far from being a plot but rather a kind of skeleton to hold up the eyes and ears and fingers and heart.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

The Year of What Now is about the way in which serious illness affects our lives. Whether suddenly or gradually, serious illness becomes something against which we measure our lives, as a kind of before and after, for the patient and the patients family and friends. Serious illness is so devastating, beyond its immediate physical toll, in part because it is equally personal and commonplace, which feels especially cruel.

Many of the poems concern themselves with that contrast, as played out in the hospital. To the patient, their experience is singular and potentially life-altering, while to the hospital staff each patient’s condition is one of hundreds along a tragic spectrum contained in one place. We want nothing more than to have our pain be acknowledged as unique and yet, from a medical standpoint, that would be the worst possible outcome.

Serious illness has altered my family, the people I love, in many ways. In setting out to write this book, I meant to honor those who’ve endured if not survived and also to honor the truth of the experience without attempting to speak for anyone but myself. I think it’s a book I had been trying to write for most of my writing life but I didn’t realize it or didn’t know how.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

It was very important to me that each poem was able to stand on its own. The way I think about the book is that the “story” reveals itself to be a story as more poems accrue. But I didn’t want that accrual to be only linear. I wanted to make space for moments of abstraction, tangents, etc., and so I saw it as an imperative that each poem had to operate as an individual unit. I think of the book as a whole as one of those mosaic images whose pixelated whole is comprised entirely of smaller pictures. The poems that relied on other poems to operate were the first ones I cut.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

Full immersion. When I set out to write this book I was effectively abandoning the manuscript I had been working on for the past four years, which suddenly felt soulless and cold to me. Dumping my old manuscript was an incredible motivator. I had to start from scratch. I gave myself 6 months to write the new one. The timeframe wasn’t arbitrary—this was in January and I wanted to have the new book ready to go by the fall. The idea for the book was there inside me (and suddenly appeared all around me) and at times I felt like I couldn’t write fast enough to get it all down. I set out to write 90 poems with the idea that I would keep maybe 60 of them. It was probably the first time in my life that I truly felt I was putting in the work it takes to write something worthwhile. I felt excited about writing in a way that I never had before. The accelerated timeframe also helped curb another problem of mine—thinking instead of writing. When you have to write a poem every other day, you don’t really have time to consider what’s worthy of being written; you just write.

What effect do you think the prevalence of project books is having on poetry in general?

To me, the “project book” has been around since the beginning. The Iliad, The Aeneid, The Inferno. Don Juan. You could argue Leaves of Grass is a project book. Four Quartets definitely. How about Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings? Annie Allen. 77 Dream Songs. The Changing Light at Sandover. The Wild Iris. Autobiography of Red. Native Guard. I would argue anyone working in this particular vein is part of a fairly long tradition.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

You have no idea the anxiety these questions provoke in me at the moment. Thanks a lot! For a long time after I finished writing the book I didn’t write anything at all. At first, I told myself that it was okay because I’d just written more furiously than I ever had in my life and was allowed a break. Three years later I’m out of excuses. I’ve begun writing again—this year has been more productive—but I feel aimless in a way that’s unsettling. I’m trying to dig into that feeling of being unsettled and write from that space, but it’s been hard. It’s a lot of fits and starts. I’ll write three poems in a day and then none for weeks, and during those weeks I’ll truly feel like I’ve forgotten how to write a poem. Like I don’t know how they sound anymore. So, I’ll say the transition is ongoing, still trying to figure out what I’m trying to do. Trying to learn to give myself permission to write garbage and trust in the act of writing that I’ll come out alive.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

Aside from the fact I could use some advice myself, I would say don’t rely on any one example for writing. If you try to have one kind of book in mind as a model for your writing the best thing you’ll ever produce is a copy of a copy. The wonderful and sometimes maddening thing about poetry is that there is no single precedent for what a book of poetry must be. Perhaps I’m biased but I think poetry has a wider field of vision than other forms of writing, can live as variously as possible. Take advantage of that. And don’t limit yourself to poetry only for examples. Never stop seeing yourself as a student.