Book Title, Press, Year of Publication

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication

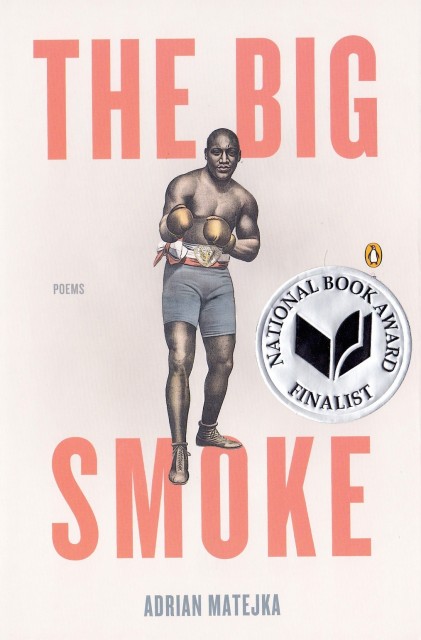

The Big Smoke, Penguin USA, 2013

Synopsis: This collection of poems examines the life and mythology of Jack Johnson (1878-1946), the first black heavyweight champion of the world.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

I think project books come from a combination of fixation and poetic stamina. We all have our personal fascinations and it can sometimes be tough to negotiate them in any cohesive way. But if a writer has the right kind of interlocking imagination and the stamina to fully explore those subjective or emotional fixations, what comes out of that can end up being a project book.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

I’ve been a boxing fan since I was a kid, but I didn’t know very much about Jack Johnson. My mother talked about him all of the time, though, and when I started my research, I thought I was going to write an essay about watching boxing with her. Once I got into Johnson’s story, I realized that the history around the man was urgent and immediate and it needed to be considered in a way that would allow Johnson himself to have some kind of say in the matter. The poetic monologue seemed like a natural form.

Here’s the thing. Jack Johnson is basically a forgotten figure, even though he was one of the most famous—or infamous, depending on perspective—people of his time. He is so past-tense that during early readings from this project, I had to clarify that the speaker in the poems is Jack Johnson the boxer, not Jack Johnson the Curious George singer. So the book ended up being an opportunity to remind people of who Johnson was and celebrate his accomplishments. It was also an opportunity to rectify some of the misinformation around him. Many of the people I’ve met who are familiar with Johnson only know him through Howard Sackler’s The Great White Hope, which is an inaccurate appropriation of the prize fighter’s biography.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

The obligations of the individual poems in this book are different from those in a traditional collection of poems because of the narrative structure. Pretty early on I stopped thinking about the poems as stand-alone events (as I expect in a traditional collection) and started thinking about them as fragments of a character’s story. I tried to develop the poems in service to the speaker’s narrative position in the book, rather than the poetic unit. So I thought about the ways in which a poem furthers the overall narrative first; the character’s arc in the book second; and lastly, how the fragment operates on its own.

The parallel question to this one might be how each character or voice stands up in relation to—or separate from—the other voices in the book. I’m not sure about that. The poems in Jack Johnson’s voice were the only ones that appeared alone in magazines. All of the other voices had to be paired with Johnson’s to create a historical or narrative conversation.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

It took me eight years to write the book, but I was working on different projects the entire time. I had to keep moving artistically because Johnson’s universe is so alluring. He was a 21st-century athlete living in Jim Crow America, and there are poetic opportunities all up and down the anecdotes and myths surrounding him. There is also the issue of working in voices from the turn of the 20th century. The language is full of surprises because so much of the vernacular didn’t get recycled. For example, they used to call mouth guards “gum shields” and cars were called “pleasure machines.”

It would have been easy to lose my own poetic persona—whatever that is—if I hadn’t continued to inhabit 21st-century language. So I worked on Mixology while I was working on The Big Smoke. I would research or sketch material for the Johnson project until I felt like I was getting overwhelmed, then I would switch to the more lyric work in Mixology. Early in the research, I thought the Johnson project would be my second book. But when I started writing the poems, it became clear I was going to need a significant amount of time to show his biography the proper deference.

Do you have a sense of whether the fact that this is a project book helped position it to find publication more easily? Has it helped you find readers?

I am very, very fortunate because I have an editor and publisher who support my work. They were willing to take a chance on this book in spite of the fact it is so different from anything I’d tried (or will try again, for that matter). The positive response to the book is the result of Jack Johnson—his charisma, his infamy, his mythology. Even though he’s been forgotten by most of the American public, his story is fundamentally American. He came from nothing and worked to get everything he wanted. Because of him, the book is easy to summarize and has a kind of narrative arc that traditional poetry collections can’t have. There is no question the subject and shape of the book has been crucial to it finding an audience.

As a reader, are you drawn to project books? What project books have influenced you or have you enjoyed, and what do you think makes those books successful?

I’m a big fan of project books because they offer an opportunity to make a poetic fascination three dimensional in a way that individual poems are unable to. There are so many project books I admire. But for the sake of this question, I just want to list a few (and there were many more than this) that I read for inspiration while I was working on The Big Smoke: Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s Apocalyptic Swing, Tyehimba Jess’s Leadbelly, A. Van Jordan’s MacNolia, Quraysh Ali Lansana’s they shall run, Oliver de la Paz’s Names Above Houses, and Patricia Smith’s Blood Dazzler.

What effect do you think the prevalence of project books is having on poetry in general?

About 10 years ago, I had the honor of being included in the Poetry Society of America’s Festival of New American Poets. Every writer at the event was between his or her first and second books. There were some amazing poets there—Lyrae Van Clief Stephanon, Sherwin Bitsui, Ilya Kaminsky, Oni Buchanan, Thomas Sayers Ellis, and many other wonderful, inspiring writers I won’t name because this already sounds like I’m trying to big time. But here’s the thing. Almost every writer who participated was reading from a project and many of those projects are out in the world now as books.

I didn’t think about the pervasiveness of projects at the time, but in retrospect, it all makes sense. Developing an idea over a cycle of poems or book is a natural reaction to the more individualized poetic moments we usually start out writing. But even if a poet isn’t consciously interested in more expansive connections between poems, we’re all writing in the contrails of project books. Paradise Lost and The Inferno are project books. As are John Brown’s Body, Thomas and Beulah, Garbage, and many others. So even before I started to conceive this project about Jack Johnson, I was being exposed to different synaptic connections for poems in the books I read—voice, form, narrative arc, and the rest.

The new challenge has been moving away from thinking of collections as projects. As I’ve been working on my new book, I’ve had to fight to keep the poems from becoming cycles. Everything I write seems to be looking for a poetic friend or two to hang with. The book might become a project in the end anyway, but I’m trying to find ways to let the poems congregate naturally.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

The fundamental need of poetry—as in this poem needs to be written for reasons bigger than hubris or artistic Tetris—applies regardless of the text’s shape. If the poems don’t live lives of their own, rethink the approach. No matter how tuned in we might be to the subject, a project isn’t enough of an excuse for a poem to exist. There has to be something more on the sum side of the addends for the poem to have value.