JESSICA JACOBS’ poetry, essays, and fiction have appeared in publications including Beloit Poetry Journal, The Missouri Review, Rattle, The Oxford American, and the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day series. An avid long-distance runner, Jessica has worked as a rock climbing instructor, bartender, and editor, and now serves as faculty at Writing Workshops in Greece and as the 2016 Hendrix-Murphy Writer-in-Residence at Hendrix College. She lives in Little Rock with her wife, the poet Nickole Brown. You can find more of Jessica’s writing at www.jessicalgjacobs.com. JESSICA JACOBS’ poetry, essays, and fiction have appeared in publications including Beloit Poetry Journal, The Missouri Review, Rattle, The Oxford American, and the Academy of American Poets’ Poem-a-Day series. An avid long-distance runner, Jessica has worked as a rock climbing instructor, bartender, and editor, and now serves as faculty at Writing Workshops in Greece and as the 2016 Hendrix-Murphy Writer-in-Residence at Hendrix College. She lives in Little Rock with her wife, the poet Nickole Brown. You can find more of Jessica’s writing at www.jessicalgjacobs.com. |

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

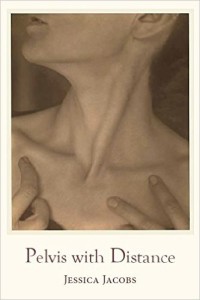

Pelvis with Distance, White Pine Press, 2015

Synopsis: A biography-in-poems of the artist Georgia O’Keeffe, interwoven with prose poems about the solitary month spent by the author in New Mexico’s high desert while writing this book.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

For me, project books fall into two distinct categories. The first is a collection whose poems flock tight around a handful of subjects, shepherded by some overarching theme. These are cohesions bound by likeness, by a binding obsession. Examples include Matt Rasmussen’s gorgeous Black Aperture, which, by circling like an anxious dog around the devastation of his brother’s suicide, becomes an extended exploration of grief and healing and what it means to be the one left behind; as well as Andrea Cohen’s Furs Not Mine, which, following the death of Cohen’s mother, treads territory similar to Rasmussen’s, yet is distinctive for Cohen’s idiosyncratic brand of gut-punching black humor.

The second category, in which my book resides, is a more hybrid territory, one that defies the clean distinctions of bookstore shelves by hitching longer works to the modifier, “-in-verse” (think Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red: A Novel in Verse). Similar to Adrian Matejka’s The Big Smoke, which is built around the life of the prizefighter Jack Johnson, Pelvis with Distance is a biography-in-poems based in extensive research and aimed at capturing truths about its subject that are both factually and emotionally resonant. These are cohesions bound by narrative, gaining energy and momentum from stories told in full.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

Midway through my MFA, I found myself in the Indianapolis Museum of Art, stopped cold by O’Keeffe’s painting Pelvis with Distance: in the foreground, a massive pelvis seemed to float before a small blue range of desert mountains. Outside, it was winter. I’d moved to Lafayette, Indiana, from Manhattan, where I’d quit a steady corporate publishing gig in hopes of a new, more fulfilling life writing and teaching. I was 30. I was alone. I was struggling with what it meant to live as a writer, to make the choices necessary to pursue what I cared about most. And here was this 70-year-old painting with a compelling title that was somehow more alive than any of the contemporary work around it.

I went home and read everything about and by O’Keeffe available in Purdue’s library. I visited the O’Keeffe archives in Santa Fe and saw as many of her paintings in person as I could. And what I found was a woman who from the first knew she wanted to live a life devoted to art and who, again and again, despite countless obstacles and reasons she should have failed or given up, demonstrated the will and discipline to see that life through.

So, simply put, I wrote these poems because they were the ones I had to write to make it through that time. In coming to understand O’Keeffe through writing poems in her voice, I came to a far more thorough understanding of myself—both who I was and who I wanted to be.

Are you comfortable with the term “project book”?

Though certainly not the sexiest term, sniffling as it does with connotations of the grade-school science project (I, for one, investigated acid rain by feeding plants aspirin-laced water, dutifully recording the growth of my little shoots), I’ve yet to hear anything better. However, the etymology of project, courtesy of Google, at least gives it a little more texture:

from Latin projectum “something prominent,” neuter past participle of proicere “throw forth,” from pro-“forth” + jacere “to throw.” Early senses of the verb were “plan, devise” and “cause to move forward.”

As a reader, project books achieve prominence in my memory over more disparate collections because I can sink into them as I do a novel, to lose myself to their particular world, and emerge with the feeling of having experienced something of depth, something that will stay with me. And, as someone who can get cranky with conventional novels for their use of cliché and extraneous words, the bonus here is you also get a poet’s word-by-word attention.

As a writer, I’m particularly taken by the idea of a project moving something forward. Though I love that a poem can be about anything, I also often find that idea paralyzing. After writing the initial O’Keeffe poems, I created a narrative outline as I would for a novel, noting moments from her life that could act as starting points for poems. Though, in the end, I often combined these or included them in a different order, it meant that each day when I sat down to write, I always had a sense of what might come next, which I found incredibly generative.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

To write the majority of these poems, I holed up with six months’ worth of notes in a small primitive cabin in the New Mexico desert, in the same area O’Keeffe spent the final half of her life. Living alone for a month with no electricity, phone, or internet, with my closest neighbors a five-mile hike away, was both one of the best and most difficult things I’ve ever done. In the year that followed, while I revised the completed manuscript, I wrote an essay about my time in that cabin.

Fast forward to January of 2014: I’d finished my degree, gotten married, had a job teaching in Arkansas, and I’d just received the happy news my book would be published in spring of 2015. With a year to publication, I once again began to revise, irked by the certainty my book was missing something. Over lunch one day, my wife and our dear friend, the brilliant poet Laure-Anne Bosselaar, decided that what was missing from the book was me. Why did I care enough about O’Keeffe to write an entire book about her (and, as a corollary, why should the reader care, too)? Here I was, exploring someone else’s life, but what did I have at stake?

To answer these questions, I returned to that cabin essay and extracted a series of prose poems that allowed me to interweave my story with O’Keeffe’s, framing her life with my own. So, though I thought I was allowing my attention to wander, everything I wrote during that time floated up from the same well.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

If, in some ways, writing Pelvis with Distance was a way of looking out as a roundabout way of looking in, the poems I’m writing now leave out the middle man (or woman, to be more accurate). That is to say, I seem to be about a third of the way into a lyric memoir (in-poems, of course) about my relatively new marriage. Though my wife and I met in 2007, we spent six fraught years apart, and then, after finally getting together in 2013, were married within six months. This meant that though I knew I wanted to spend the rest of my life with her, when it came to the day-to-day, I couldn’t name her favorite flavor of ice cream, how she took her coffee, or how best to move from conflict to compromise. These poems explore the years that have followed.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

When first working on a series of linked poems, it’s helpful to turn to prose. What are books that had you from the first and held you to the end? Break them down. Map the trajectory of tension, of how the story moves through time. List the moments crucial to the plot and those that can fall away. Pinpoint the ways in which you come to know a character (descriptions, actions, dialogue, etc.). Poems have that same ability to build narrative and create characters, and outlines cribbed from novels or memoirs can act as your guides.

But as Eleanor Wilner wrote, “What is often called ‘inspiration’ in art is, more accurately, obsession: it is what gives life to language.” To sustain a collection of linked poems, it’s vital this element of obsession burns bright. So I guess my best advice is the one I often give myself: be open to what moves you, what forces you to stop whatever it is you’re doing and put pen to paper. And, once found, don’t be afraid to follow as far as it will take you.