Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

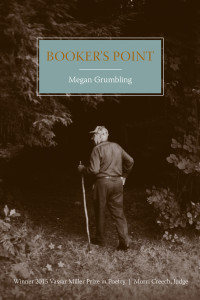

Booker’s Point, University of North Texas Press, 2016

Synopsis:

Booker’s Point is an oral-history-driven portrait-in-verse of an old Maine woodsman, told in conversational formalism, and a meditation on place, nature, work, and elders.

Watch the trailers here and here.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

I think of a “project book” as basically a concept album of a book, a book that evolves and holds around a central subject or idea, and whose creation has been driven in pursuit of better understanding that central subject. In Booker’s Point, that central subject is Bernard A. Booker and his landscapes – including southern Maine’s Ell Pond, nearby fields and woods, old deeds and town lines, and the settings of geographical memory. Pursuing the poems in this book drew me into an exploration of the man and the place, with an eye to learn what I didn’t know, to preserve some fading ways, and to grapple with some more universal questions and challenges of home and how to live in it.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

I was drawn to Booker as a subject when I first returned to Maine, after years of being all over the place during college and grad school. I was primed to relearn home – and to acknowledge the many gaps and misconceptions in what I knew of “home” – and Booker was a wry old woodsman who knew everything about it. So I immersed in him, his stories, and his work: partly to record (what I thought would be) an oral history of the land around Ell Pond, and partly as a way to re-immerse in home. With Booker I dug holes in the ground, looked for good white stones in the woods, and heard a lot of stories – both the pastoral and the less idyllic – about where I’d grown up. In the process, I so deepened and complicated what I knew, and found such connection with him and our elemental chores, that I knew that I needed to process it all through poetry instead.

Was your project defined before you started writing? To what degree did it develop organically as you added poems?

As I mentioned, Booker’s Point actually started as a straight oral history project. I recorded hours of tape interviewing Booker while he and I were tromping around, I transcribed all of it, and I culled it by themes (“history,” “trees,” “work,” etc.). Though I’ve written poetry since I was young, I’d studied oral history and ethnography in college, and had just finished grad school in journalism, and I first thought my final product would just be selections from the transcripts, curated into sections by theme. The first poems came when I found myself becoming more than a documentarian, feeling myself moved, recognizing scenes and ideas I wanted to get my hands into, to work with more than straight oral history would ever allow. So my work in the first draft developed via an interesting tension between documentary impulse and more lyrical narrative, between the transcript’s stories and my own experiences.

As the first draft developed, I focused almost entirely on the portrait of Booker and the place. Then, one of my readers along the way insisted that I was an inherent part of the project, and that my own motivations and experiences as a character and voice needed to be in there. That insight began a big overhaul on the book, and a lot of new searching and different poetic styles. It also turned up inevitable ambivalences – darker or less sure or less pastoral inklings. All of this has, I think, made it a much more true, nuanced, and interesting book.

At any point did you feel you were including (or were tempted to include) weaker poems in service of the project’s overall needs? This is a risk, and a common critique, of many project books. How did you deal with this?

I had to cut a LOT of poems. Given that I’d started with something like ten hours worth of stories and history, you can only imagine! There was so much ground I wanted to cover. Many of the poems that got axed were illustrating some angle of Booker or the landscape or the history that I really wanted to get across, but that just couldn’t hold and glow beyond the sum of their parts like poems must. Often these cut poems were more expository than felt, and couldn’t manage the crucial synthesis of idea, thing, and feeling. It took me a while to give up on some of them, but ultimately doing so was a good lesson/reminder about what poems should do, and an important affirmation of the failing that we all do all the time as writers.

As you were writing, were you influenced by your experience or perception of how project books are received by readers and editors (either positively or negatively)? Do you feel differently about your book being defined as a “project book” now that it has been published than you did when you were writing it?

The one concern I have had about Booker’s Point being known as a “project book” is that I worry the “project” might be defined in a too limited way. Namely, I hope it will be seen not as a work of unalloyed regionalism or nostalgia about one Mainer, but as a project that tries to deal with subtler and more universal questions as part of its portraiture. I find myself thinking about that more now that it comes to promoting the book, and I guess it’s my job in promoting and reading to try to make all this clear – though as we all know, sometimes it’s tricky in a brief blurb to set up the project in a way that frames necessary context without drawing too strict of a box around it. At any rate, I do have a sense that readers (and listeners at readings) really long to settle into and immerse in the intimacy and many dimensions of a project book, and I’ve been gratified by that reception of Booker along the way of the publishing process.

As a reader, are you drawn to project books? What project books have influenced you or have you enjoyed, and what do you think makes those books successful?

I am very strongly drawn to project books. I love the focus and intimacy of these books, the capacity to immerse in material that has engrossed the author, the depth of field they allow me as a reader and learner, and the new lens I develop from my reading – a new tool for seeing the world. Some of the books I’ve enjoyed:

Arra Lynn Ross’s Seedlip and Sweet Apple, a meditation on the Shakers’ founder Mother Ann. Cynthia Lowen’s The Cloud That Contained the Lightning uses as a lens the character of J. Robert Oppenheimer (the “father of the atomic bomb”) in a fascinating exploration of the history and legacy of nuclear weapons. And as a poet who’s fond of oral history, I was captivated by the late C.D. Wright’s remarkable One With Others, a portrait – as she put it, “a report full of holes” – of her late mentor “V.,” a white civil rights activist who was thrown out of her Arkansas town for her views. Part of what makes all of these books successful, to my mind, is how widely and variously the authors have constellated their subject matter – through a range of voices, materials, styles, and tones: Ross gives us the imagined voice of Mother Ann, interwoven with words from newspapers, Gospels, and Shaker texts; in Lowen’s book, we hear from both Oppenheimer (studying surrender, getting caught in a blizzard) and the “Hibakusha,” or “explosion-affected people” of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And Wright interweaves the voices of V. with that of radio ministers, senators, and the local veterinarian, jokes with “Dear Abby” columns and grocery prices, in a rich conjuring of the culture.

Have you abandoned other project attempts? How did you know it was time to let go? What happens to project poems that never amass a full-length book?

I’ve definitely started poems around a center that ultimately didn’t have enough gravitational pull to hold the project. When I found myself really reaching to make those poems make sense together, I knew it was time to let go. I don’t know what happens to those poems! Years ago I had this Andy Warhol series that was meant for a totally diffuse project book (it also included Johnny Appleseed and Buster Keaton, to give you a sense of the scope of the diffusion!). Years after abandoning it, I saw a call for pop-culture poems and got a Warhol poem published, and I was like, Huh. It had never even occurred to me that maybe these poems could go out into the world without being part of a whole solar system of other poems. So maybe there’s hope.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

I’m a serial project writer, and I tend to be mulling a new scheme as I’m finishing up a project. Right now, I’ve just finished the libretto of a new spoken opera that premieres this May in Portland, Maine; it’s a re-telling of the Persephone myth in the age of climate change. It started as a book project and then became an opera, and now I’m trying to get a full book version of it together, which is kind of a weird/hard/interesting series of shifts to make – page to voice and back to page again. I hope it works! After that: for about ten years I’ve had an idea for a kind of hybrid novel that I’ve always been afraid to jump into, and I think I might finally just try it and see what happens.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

Zoom in and out often in your view of the project. Be willing to play with different and unexpected forms and styles that might present themselves along the way. Keep track of your shifting approaches to the material, of what you abandon and what you discover. Keep a project journal – it can both document your process (often very useful when the project winds up taking several years) and provide free writing therapy! I also find it helpful and reassuring to think of a project book as with the French sense of an essay, an essai, or a “try.” That is, the spirit of the thing is to seek to learn the subject through the writing itself, approaching with curiosity and a beginner’s mind.