Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

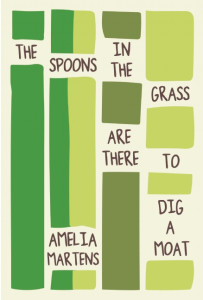

The Spoons in the Grass are There to Dig a Moat, Sarabande Books, 2016

Synopsis: These prose poems push between the extraordinary ordinary, our little and big world problems, and direct attention to the surreal mesh of our realities.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

I see a project book having some overarching organization; this could be a theme or form or threads that are braided together to move around a topic while shifting points of view. My book works with the prose poem as a unifying form, but it also contains two main threads: the Jesus poems and the “our daughter” poems—both threads operate in the same world, but the point of reference shifts.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

After our first daughter was born, the prose poem started coming to me in full force. Simply, I did not have time to fret over the line and was so desperate in my need to write under the duress of new-motherhood, that I ran with what was coming so as not to shut progress down via the editor in my mind. As I investigate the prose poem more fully, I see that there are likely several reasons, beyond the time constraint, that the prose poem came to me. This form is versatile, subversive, narrative, allows for play with the structure of a sentence as a rhythmic unit. And women writers have been creating a much wider range of poems in this form than I was previously aware—see Holly Iglesias’ Boxing Inside the Box. The Jesus poems are a result of living in the hyper-religious landscape of western Kentucky and in this time. The “our daughter” poems are fragmented glimpses into daily living with our two daughters, Thea and Opal. These two main threads allowed me to switch my approach and move to another way of looking if the poem wasn’t working.

Was your project defined before you started writing? To what degree did it develop organically as you added poems?

No, this project developed organically—probably about ¾ of the way. It wasn’t until I had a giant pile of prose poems that the idea came to me that these could be a book. It sounds weird, but all I was getting from the universe was prose poems for a couple years—maybe a lineated poem snuck in here or there, but I didn’t have time or energy to investigate the phenomena—our daughters are two years apart and when I sent the manuscript out for the first time (to Sarabande Books who accepted it!) our daughters were 1 and 3—life was full, so I took what came and it happened to be prose poems following two main veins.

Do you have a sense of whether the fact that this is a project book helped position it to find publication more easily? Has it helped you find readers?

That the book is all prose poems with two main threads offers the reader a chance to read in one (unassuming) form and return to points of view and subject matters that at least appear consistent throughout. I know the prose poem attracts some readers and repels others. I know there are some readers that will be pulled in by the daughter poems and reject the Jesus poems or some who will be attracted to the Jesus poems and less interested in the daughter poems—and of course those who fancy both or are thoroughly appalled all the way around. I think the consistency of form and themes make the book easy to access—readers can get inside, perhaps, before they realize that these are poems. The consistency and skewed worldviews make this an easy book to talk about, and to read from; both aspects probably helped it find publication so quickly.

As a reader, are you drawn to project books? What project books have influenced you or have you enjoyed, and what do you think makes those books successful?

Yes, as a reader I find “project books” intriguing—mostly I like the extended gaze they present; it appeals to me to not look away for a whole book. I left grad school feeling like my book would have to be a project book, since that is how I viewed my thesis (all Amelia Earhart poems—she totally made it to an island). For me, it was easy to see how poems fit into those sorts of books—the relationship between the poems was clear from the start. I think my book is more formally related, but I see now that there are clear connections to a specific present-day American existence. A panel I attended at this year’s AWP brought up the idea that thinking of any book as a “project book” can be useful or not useful to the writer; if I’d thought about my book as a “project book” while writing these poems it probably would have shut me down—so I just thought about each poem, but now that it’s done I can see it as a “project book.”

I have enjoyed: Maurice Manning’s Lawrence Booth’s Book of Visions and Bucolics, Nick Flynn’s Blind Huber, Mitchell L.H. Douglas’ Cooling Board, Alexandra Teague’s The Wise and Foolish Builders, Nin Andrews’ Why God is a Woman, Micah Ling’s Flashes of Life. These books are successful, for me, because they build worlds, and each functions sort of like a zoetrope.

What effect do you think the prevalence of project books is having on poetry in general?

In some ways, the project books are providing openings to poetry for people who may not otherwise pick poetry to read—if the book centers on a person or area of interest for the not-poetry reader. I worry though that writers may be starting to think they need to confine themselves to an easy to describe or digest structure or theme or topic in order for their book to be published. In my mind, all books are project books—in terms of being objects constructed over time; however, it seems we use the phrase more to describe books which appear more easily consumable—these are poems about the Winchester house, these are poems about an island where women rule, etc. This does a disservice to the complexity of the books, but it also breaks down the immediate reaction to reject poetry for those who are less familiar to the arena.

Have you abandoned other project attempts? How did you know it was time to let go? What happens to project poems that never amass a full-length book?

Yes. My first chapbook, Purgatory, oddly also made up of prose poems, needed to be a chapbook because the poems’ intent is to make the reader uncomfortable. I realized after reading through these poems that they couldn’t be sustained for a book; the reader would want to escape and I wanted to give them just enough that they’d keep reading, but still be itchy and constricted. In a shorter format, these poems accomplish their goal and it felt like overkill to extend any further. This happened with each of my chapbooks—the drunken-Santa Claus-in-exile could only be sustained for a chapbook (Clatter) and the painful family poems, even with the semi-uplifting seismologist character, were too much in a full length collection (I tried it for a couple years without success—so cut all the “fat” and made a chapbook—A Series of Faults, which got picked up right away).

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

Be open to the poems that are coming to you. Maybe you have a “project” and don’t know it (like I did); don’t force it. If thinking of your work as a “project book” helps you write poems, allows you access to your words, helps to clarify, then think of your poems as fitting into a structure. If “project book” shuts you down, if it feels constricting to think beyond just this poem you are writing—then let the term go. You may still end up with a “project book.” Good writing is good writing—aim for that instead. Also be open to the idea that one project may lead you to another project. I think this happened for me with the Jesus poems having been seeded in my head by my purgatory poems.