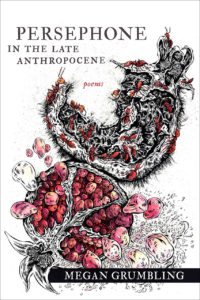

Persephone in the Late Anthropocene, Acre Books, 2020.

Synopsis: Persephone in the Late Anthropocene vaults an ancient myth into the age of climate change through lyric verse, magical-realist prose poems, and speculative crypto-studies of the Anthropocene, as the goddess comes and goes erratically from our warming world.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

Persephone coheres around a guiding question: how the ancient myth might be updated to the age of climate crisis, extreme weather, and erratic seasons. It explores that central inquiry through a variety of voices and modes – goddesses, humans, pop anthropologists, a New Farmer’s Almanac. That’s how I think of any project book: one that’s driven by a particular question that the poems individually and collectively explore, in the spirit of an essay.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

The premise of Persephone – the question of what happens to the myth in the age of climate crisis – is one I’ve been thinking about for years. Much of what I write has long concerned either the environment or the idea of story, and as the effects of climate crisis have become more and more evident around us, I’ve grown increasingly absorbed with the question of how we tell its story. Narrative has a fundamental role in how we understand and react to anything, especially conflict. So I think the growing urgency of the question is what finally made my ideas around the project begin to cohere and gain momentum.

Was your project defined before you started writing? To what degree did it develop organically as you added poems?

I noodled around with the premise of Persephone every now and then for about a decade, making notes for how it might play out in different modes – an essay, an experimental film. Nothing stuck or felt right. When it finally started coming for real, it first came in the form of some strange little prose poems, a form I’d never written in before. The range of forms and voices evolved from there, as I kept coming back to questions about the different voices that might be telling this story and how they might tell it.

And when I was only a few poems into the project, my creative partner – composer Denis Nye – and I agreed that we would work Persephone toward a full-length experimental opera. So the poems also developed apace the performance aspect of the project, which we staged gradually: first just the first five poems, then the first movement, and finally all three movements. And so as I wrote further along, I was able to respond to the music and what we had already staged, the other artists’ interpretations of the words. That collaborative dynamic has been such a gift to me a writer.

I always knew that the project would eventually become a book, but the immediate need was to write poems that would be in people’s mouths onstage and play well with music and movement. And so although the opera we were creating was non-traditional in many ways, the needs of performance and at least some basic dramatic conventions definitely shaped the work.

There were also pieces that I was writing early on but that I knew couldn’t go in the performance – they were fun but too dense to take in aurally, definitely meant for the page. It was fun to come back to them later and brush them off.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

Project-wise, I was 100% immersed in Persephone for about three years, creating both the poems and the opera. But I was often working on other aspects of the project simultaneously with writing – counting off beats and breaths with the composer, casting actors, going to rehearsal, applying for grants. It was an intense process, but also such a joy to be working as part of a team and working lots of different muscles of process and craft.

As a reader, are you drawn to project books? What project books have influenced you or have you enjoyed, and what do you think makes those books successful?

I am super drawn to project books. One I’ve loved is Tyehimba Jess’s Olio, which blew my mind with its formal innovation and with how prismatically it explored the phenomenon of Black American minstrelsy. Another is One With Others, CD Wright’s lyric portrait/oral history of her civil-rights-activist mentor. Another is Arra Lynn Ross’s Seedlip and Sweet Apple, a beautiful meditation on Mother Ann Lee, founder of the Shakers.

I think what makes these and other project books so powerful to me is because I love a poetic deep dive into a subject, and I also love seeing how other poets navigate their own deep dives. It’s especially exciting for me to see how the subject has shaped the poet’s forms – whether inventories, “syncopated sonnets,” or documentary snippets. I have the sense in these books of how completely the poets gave themselves to their inquiries, exploring both the subject and what their own craft can be and do.

What effect do you think the prevalence of project books is having on poetry in general?

I think the rise of project books sees poetry contributing to cultural inquiry and social criticism in increasingly focused and sustained ways. And because poetry is so myriad, protean and often liminal in its forms, the poetry project book is perhaps even better positioned than, say, the long-form essay to explore a theme or problem from many angles and through different lenses. I think the project-book phenomenon brings important voices and perspectives to our most difficult and vital conversations – and also offers, of course, many fascinating deep-dive diversions.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

My advice is to give the project lots of time and space, enough that it can show you where it wants to go. Make time for play and going down rabbit holes. Let it take you to forms you find weird or uncomfortable. Persephone is profoundly different in form than my last book, which is also a project book. I might still be noodling my way around the Persephone premise if I’d resisted those strange little prose poems! “Let the work show you how it’s done,” I once read inside the cap of a bottle of cheap vodka, and for me, nothing could be truer of project books.