Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

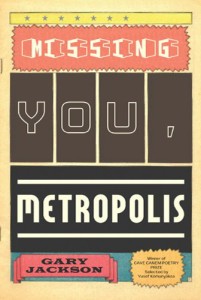

Missing You, Metropolis, Graywolf Press, 2010

Synopsis: Two black boys who are childhood friends struggle to escape from Kansas: one through death, the other through comic books and superheroes, and neither works perfectly.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

Ooooh, this is also answering another question later on the list, but I’m not entirely comfortable with the term “project book.” It strikes me as reductive, though I realize there are folks who go out and say, “I’m going to write a book about ____.” I have no real defense for why the term “project” makes me run away. In college, in an American Literature course, we had to create a project — that accounted for 20% of our grade — the only guideline was that it had to connect to the texts we had read during the semester. I hated it (though I loved the professor). A student in class made a board game — similar to the game of LIFE — and it was crazy intricate and cool. She offered to call me her partner so I could also take credit for the project, but I refused, not because it was morally right, but even her freebie project made me uncomfortable. In the end I recorded my friends reenacting a particular massacre we had read about (which I’m now forgetting). It was horrible and I’m sure without a doubt, extremely misinformed and thoughtless. I can’t remember the grade I received. And now I’m starting to doubt that was even the project, it may have been for another assignment altogether (in which case those same criticisms still stand), which means I’ve completely forgotten what I did for that project. This is all to say I run from projects. Though my book is very much considered a project book.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

Now I’m cheating and answering the previous question for this question. My book has an obvious narrative arc (growing up in Kansas), and clearly involves comic books (especially superheroes — in the form of persona poems), though I never thought or believed I would publish a book primarily consisting of those two equal parts surreal/sobering worlds. All I can say is at the time I was obsessed with comics and superheroes, and obsessed with my ghosts. I still am. Missing You, Metropolis has some elements of a project book, in the sense that once I had a solid draft of the book nailed down, I did go back and revise and write new poems to pick up threads that got lost in the shuffle. And the previously mentioned narrative arc/thread that runs throughout the book. But there are also non-project elements, I’d argue: I didn’t write the poems thinking those superhero poems would in any way connect to the more autobiographical/Kansas/childhood poems, and even then, I didn’t realize I was going to write a majority of the poems I was going to write until I was already writing them. My obsessions were pressing on me, and by the time I wrote them out, I had just barely enough (decent) poems for a book. And even that’s a lie: I’m still writing out those same obsessions; if anything, my entire career, thus far, is a project. And in Missing You, Metropolis there was a fairly large expanse of time between the oldest poem and the youngest: about eight years. Though that doesn’t mean anything, really, all it demonstrates is that I was not aware of how these various poems were going to talk to each other until I sat them all down in a room. But that’s probably most first books, right? Especially those first books that are essentially your dissertation — you don’t even know what the hell your book is going to look like until you’re in it. I didn’t know.

Are you comfortable with the term “project book”?

Not for my own work. Primarily due to the fact that it causes me to panic: as soon as I write a couple poems that have a shared theme/structure/conceit, I immediately think “Hey! I could write a series of these poems. That could work.” And as soon as I think that, I’ve fucked myself. I feel closed in. I’ve pretty much guaranteed I’m going to lose interest. Huh. Maybe I have commitment problems.

And as I type these very words, I’m very much at work on a project book. So I’m a huge fucking hypocrite. It’s a collaborative effort, however, and I’m not sure how to work with someone without having some sort of goal/plan in place. But based on what I said above, maybe it’s already doomed to fall apart. Ha!

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

I do believe every poem should “stand on its own” as much as it can, though I’m a fan of serial poems, of the long poem published individually in sections, in poems that very clearly need to speak to other poems. But I’m a believer in a poem’s thingness: that if I crumple it up and throw it at you, and you pick it up and smooth it out, and read it, that poem will move you in some small/large way, without any help from anything, anyone else. Now success in that is another story altogether.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

I can’t work on any one thing for longer than a few minutes. It took me about three weeks to complete this interview in 5-minute sections with three day breaks in between.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

I’ve been reading many essays covering poetics for a class I’m teaching this semester, and many of these essays revolve around a similar idea: that poetry is about fulfilling and thwarting expectations. It’s all about the surprise. So for those who are using a project book as a guiding principle, my main advice is to break as many of your own rules as you follow, and make sure you’re continually surprising yourself with your own work. If, from the first poem, we know exactly how we’re going to get to the last poem, then there may be a problem. And that same test applies if you know exactly how you’re going to get from the first poem to the last poem as well. And don’t be afraid to let those obsessions enter what is otherwise a tightly knit project. Flaws are always the best part.