Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

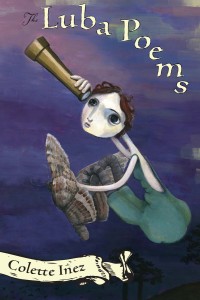

The Luba Poems, Red Hen Press, 2015.

Synopsis: The fictive Luba, a woman of ever-changing bubbles of ideas and images, a real person, yet imagined and somewhat surreal, whirls through cultures, geographies, religions, and the night sky with endless wonder, enthusiasm, and occasional sorrow.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

The Luba Poems are held together by an invented character, Luba, part real, part surreal. Invented, but also a real person who, in a loosely given narrative goes to the dentist, learns to drive a car, set up a telescope. Hers is a new feminist consciousness, sexually alert, intellectual with a fascination for celestial bodies as well as for astronomers. She muses on the name of a star in the constellation of The Southern Fish. Fomalhaut, the long “O” of her incorrect pronunciation of the name sets off a meditation.

Luba plays in Vegas where motel-wise she loses badly in the game of love. She’s a traveler: South America, Portugal, Florida. Sometimes she roves through time. She is in ancient Greece as one of Castor’s horses speeding past an arena of lovers; she is on a boat with Sappho’s daughter sailing from Athens to the isle of Lesbos. She is multi-dimensional. She is literary and dotes on the sound of words. In a jazz composer’s improvisatory art, she belts out some “scat”—“ta di, wa wa, ta ta, ti do.”

The last poem which, with its gospel sense of religious revival, suggests a resolution, or at least a new spiritual turn in a turbulent life. The reader is left with Luba’s joy, her seeming to speak in tongues and looking for that place “where singing comes from.” My hope is that the voice has grown deeper and more expansive than the “pop art” figure of the opening poem.

Luba loses her young and beloved mother in a hospital, while my own mother died in her Gascon family’s river house in France at the age of 89 without ever having acknowledged her daughter’s birth.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

Actually, Luba announced herself by intoning her name one evening in the half-light of our apartment bedroom. I seemed to be in a trance, located in that country between waking and sleeping. But I heard her name “Luba” in my head, and understood she wanted to enter my poems and that I wanted her presence. Even the sound of her name wooed me. Luba. I could let her be my doppelgänger, my twin, an extended feminine consciousness obsessed with wordplay. I could confer on Luba the excitement of Brazil and Argentina, countries unknown to me.

Her sexual adventures would be mine to conjure. And I might have a sister. As a love child, my only sisters were the Sisters of Charity in Belgium. Luba would share my love of the Shelleys, Sappho, and of Merwin whose name ends in the letter “n.” I could give her the love of stars, sky myths, and lore I share with my husband, Saul. She might be part of our cosmos. Childless, a devoted pair, we could embrace her as a fantasy daughter. I began to write poems for and about her. And I let Luba take on my voice in an assortment of poems, some in the spirit of the French “Dadaist” defying the sober and materialist conventions of society, others lyrically wired and using rhymes and off-rhymes.

Are you comfortable with the term “project book”?

The sound of it is clunky. It suggests school homework: science projects, social study projects. Something difficult or onerous. And then, one thinks of big block housing for the poor, housing projects and government projects. What’s wrong with the phrase: A Sequence of Poems on the Theme of…? Or the term: Thematic Poetry? Or describing the poems as narratives featuring this or that? We have William Carlos Williams’ episodic long poem Patterson, and the lengthy but sparely written narrative of H.D.’s Helen of Egypt as examples. And Ferlinghetti tracing the great Japanese poet Basho’s 18th-century pilgrimage in Backroads to Far Places. Also Anne Carson’s novel-in-verse The Beauty of the Husband which qualifies as narrative poetry with a unifying theme.

At any point did you feel you were including (or were tempted to include) weaker poems in service of the project’s overall needs? This is a risk, and a common critique, of many project books. How did you deal with this?

In my collection are poems of unequal strength, some put in for a connecting scene as I did in The Luba Poems when I included a poem located in an airport boarding gate. The poem that follows finds Luba in Amazon country, her love affair compared to the cracked husk of a Brazil nut.

In any case, I rarely read a book of poems straight through. Usually I get the feel of the language, the tone of what’s to come by carefully absorbing the first poem and then going onward through the collection. Although I do remember the excitement of reading Horace Gregory’s translation of the poems of Catullus, the poet’s youth in Verona, arrival in Rome, his falling in love with a counselor’s wife, Lesbia. Enthralling stuff when I first read it.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

I always work on other things. I find pleasure in being surrounded with different kinds of writings. Lately I have been working on short stories that make use of magical elements, transformations, dreams. One of these stories has been recently accepted by The Georgia Review for summer publication. I keep a journal, write blurbs and recommendation letters for poet friends with whom I swap poems for comment. Sometimes I work with composers and have had my poems set to music for piano and soprano, chamber opera and choral work. The swirl of things going on around me provides me a needed mix of anxiety and delight. I also enjoy reading star guides, and although New York City is hardly stellar-watching star country, my husband and I do take our giant binoculars out to Central Park from time to time and gaze up at the moon.

What are you working on now? Another project?

I am slowly orchestrating a collection tentatively titled FATHER father, a sequence of poems centered on my American-born Roman Catholic father, a priest ordained Monsignor the year of my birth. I hope to gather poems concerning my father and his duties to the church, his love affair in Paris with my mother, a young French scholar and Latinist with whom he worked on gathering Latin manuscripts of Aristotle’s writings, and my speculations on his early years in San Francisco where he was born in 1886. He was 48 when he died.

As you were writing, were you influenced by your experience or perception of how project books are received by readers and editors (either positively or negatively)? Do you feel differently about your book being defined as a “project book” now that it has been published than you did when you were writing it?

As I am preparing to send my manuscript out to possible publishers, I think of that book as a book, a collection of poems, a continuation and affirmation of my art as a poet. I expect others will define the poetry. I want my work to move my readers, pique their curiosity, give them pleasure. Wasn’t it William Carlos Williams who wrote: “If it ain’t a pleasure, it ain’t a poem?” I guess you can say process interests me more than analysis.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

Take pride in the language you use, even if you are bi- or tri-lingual. Love what you do, read others, stay in the shadow of excellence, read translations, enrich your life with art and music, science and dance. Keep your language fresh, alive. Don’t underestimate concision. Start your book with a poem that intrigues or mystifies the reader. I think it’s a privilege to be a poet, to have the freedom to write poetry.