Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

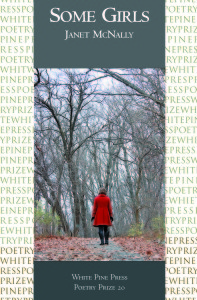

Some Girls, White Pine Press, 2015

Synopsis: The poems address what I call “girl stories,” the narratives that define femininity in our culture.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

Some Girls is built around myths and fairy tales, and in writing I tried to transform them. Of course, writers have been retelling these stories since they came into existence, so this is nothing new. That’s okay with me. I believe archetypes beg us to interact with them, and in this book I have my particular angle, my point of entry. I’ve always been obsessed with stories—I’m a fiction writer, too—so Some Girls very quickly developed a narrative arc. I had a sense of the new-mother speaker, who is a version of me, as well as her troubled best friend Maggie, who recently woke from a coma. That plot point sounds like something out of a soap opera, until you consider how many myths and fairy tales have heroines who are unconscious or asleep.

As I started writing I realized that I wanted to tell maybe fifty little stories as well as one big one, from beginning to end. Writing a book of poems is very different from writing a novel, and that’s attractive to me. I can leave some spaces empty, some dots only loosely connected. But in this case, from the beginning I knew I was working on pieces that would fit together.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

I’ve always loved fairy tales and myths, but when I found out I was having a baby daughter, I saw those stories in a different light. They were scarier, somehow, more dangerous. I didn’t know how to raise a girl outside of my own experiences, and I knew my daughter would be born into the framework of stories. When I started to think in particular about all the heroines who are sleeping or unconscious (maybe it was my new-mother lack of sleep?), I was led to the central arc of Some Girls. How could a girl in a coma (or put to sleep by a poisoned apple or bad fairy) come back the same? She’d be different; I just knew it. And the fairy tales don’t really address that.

I’m rarely interested in writing about things only as they actually happened. Can we really trust our memories, anyway? I have this conversation with my students all the time. I believe there’s as much “truth”—believable human experience—in fiction as in nonfiction. All memory comes with a filter. It’s not pure or unadulterated. So, writing with the story of the speaker and Maggie in mind—as well as that of all the familiar heroines—allowed me to reveal the truth in an off-kilter way. The speaker isn’t exactly me, but she’s mostly me. Maggie is based on some part of my identity, too: the girl who ceased to exist when I became a mother.

Are you comfortable with the term “project book”?

I love project books. It’s wonderful when a poet spins all of a book’s poems from a similar thread, and when her passions of a particular period in her life become clear as you read. I’ve been thinking about it, and almost all works of fiction are “project books.” There’s no negative connotation to that term in the world of fiction. I was surprised and interested to learn—and I say this without judgment—that some poets really resist that term. I’ve loved many collections that probably wouldn’t be considered project books, too, of course, but I really enjoy finding a book of poems that feels like a beautiful whole.

Was your project defined before you started writing? To what degree did it develop organically as you added poems?

Can I claim exhaustion and say I don’t really remember? I was writing in a frenzy, with all these brand-new emotions and experiences crowding the page. I turned to poetry because it seemed the best way to write at the time, and I needed to believe that I was accomplishing something, that I was still a writer, still me. My best memory is that the book just started to take shape in front of me, and I followed it along. There are times in our lives when we get to reinvent ourselves, and becoming a parent is one of them. This book came out of that experience.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

I’ve published most of the poems from the book alone or in pairs or trios, so I think they exist as pieces outside of the whole. That’s ideal, because poetry collections are fragmented by nature. The parts should work like individual jewels in a bracelet, or maybe cogs in a machine. Each one should be particular and necessary, but they work together to make the whole. I guess I could go full Hansel and Gretel and say that we’re hoping for a trail of breadcrumbs to lead us someplace, out of the forest or to the candy house, but it’s probably much less deliberate than laying out each crumb. Ideally the project itself and the structure of the book should reveal itself as you write.

At any point did you feel you were including (or were tempted to include) weaker poems in service of the project’s overall needs? This is a risk, and a common critique, of many project books. How did you deal with this?

Ellen Bass, who chose my book for the prize, was kind enough to give me notes and advice on the manuscript. She said—and I agree—that a leaner book is often a stronger book, and so she suggested I try to cut ten to fifteen percent of the poems. I don’t think her advice was specific to my book alone; it seemed like advice she might give most poets. To look at a collection and actively try to cut poems forces you to consider what’s working and what isn’t, which encouraged me to set my emotions aside as much as I could. I started a Word document called “Deleted Scenes,” much as I do when I’m writing fiction. It’s not as if you have to burn the rejected poems on an enormous pyre. Maybe you’ll use them again for another project or just publish them in magazines. But in most cases after I cut a poem I realized that it just wasn’t working, and I could let it go.

I also wrote some new poems after I won the prize, because by the time that happened, my feelings about the project had changed a little. By then, I had two more daughters (twins born two years after their sister). I wasn’t a brand-new mom. I had read more, lived more. So I was lucky enough that Ellen was open to my re-imagining the book a bit. She encouraged it. I feel really lucky to have had that second look, but my intention was always to keep the energy of that first experience of writing it.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

In the past, I’ve often worked on more than one thing at a time. I think it’s good for my brain. When I hit a wall with one thing, I would jump to another. I wrote many of the poems that would become Some Girls soon after my first daughter was born, and for the first time, I couldn’t really write fiction. I didn’t have the attention span for it, maybe. Poetry was so satisfying and appealing because it was shorter and clearer and more direct, and pretty much all of the poems I was writing then were related to this project. I’ve never experienced that sort of focused inspiration before. It made me believe in the Muse. Or the power of exhaustion, maybe.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

I think there’s a mourning period after you finish a project, even if you’re ready to let it go. Especially in this case. Not everything that happens to the speaker happened to me, but the emotions and ideas feel very true to me, and the book is representative of a specific time in my life. One crazy thing is that I was so worried about raising one daughter, and then two years and one week later I had twin girls! You never know what the universe will send you.

Right now I’m writing mostly fiction. I’m working on my second young adult novel as well as a novel for adults, so we’ll see which one pulls forward in the horse race. I’ve started a series of poems, probably chapbook length, but I don’t know what I’ll do for my next book-length manuscript. I think it would be interesting to write about twins, but I’m not sure exactly how yet. Really I’m just starting to feel like I can write poems again, so I’m waiting to see what will come to the surface.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

Build a house in which you want to live for awhile. Don’t try to force it, but let the walls rise up around you. That sounds dramatic, I know, but I mean it. The stakes can seem higher with a project book because if you write half of it and it flops, that can feel like wasted time. It isn’t. I’d argue that there’s no wasted time in writing; everything leads you someplace. You can learn from every mistake. It’s always been hard for me to commit to longer projects, and in this case I mostly mean novels. I’ve only finished one of those at this point. But Some Girls seemed so right at the time I wrote it that I didn’t really doubt it. I didn’t know if it would find a press or readers, but I knew I had to write it. That seems like the best case scenario: to be compelled to write.

More practical advice: Be playful. You can write about serious things without being serious all the time. Don’t be afraid to let go of poems that aren’t working or serving the book. This is true for any piece of writing. Cut it and save it, but chances are you won’t want it back once you let go. Let the book evolve; don’t try to force your poems to do things. They’re not puppets; they’re poems. They’re alive, in a way, or they should be.