NICKOLE BROWN grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, and Deerfield Beach, Florida. Her books include Fanny Says, a collection of poems forthcoming from BOA Editions in 2015; her debut, Sister, a novel-in-poems published by Red Hen Press in 2007; and an anthology, Air Fare, that she co-edited with Judith Taylor. She graduated from The Vermont College of Fine Arts, studied literature at Oxford University as an English Speaking Union Scholar, and was the editorial assistant for the late Hunter S. Thompson. She has received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Kentucky Foundation for Women, and the Kentucky Arts Council. She worked at the independent, literary press, Sarabande Books, for ten years, and she was the National Publicity Consultant for Arktoi Books and the Palm Beach Poetry Festival. She has taught creative writing at the University of Louisville, Bellarmine University, and at the low-residency MFA Program in Creative Writing at Murray State. Currently, she is the Editor for the Marie Alexander Series in Prose Poetry at White Pine Press and is on faculty every summer at the Sewanee Young Writers’ Conference. She is an Assistant Professor at University of Arkansas at Little Rock and lives with her wife, poet Jessica Jacobs. nickolebrown.com NICKOLE BROWN grew up in Louisville, Kentucky, and Deerfield Beach, Florida. Her books include Fanny Says, a collection of poems forthcoming from BOA Editions in 2015; her debut, Sister, a novel-in-poems published by Red Hen Press in 2007; and an anthology, Air Fare, that she co-edited with Judith Taylor. She graduated from The Vermont College of Fine Arts, studied literature at Oxford University as an English Speaking Union Scholar, and was the editorial assistant for the late Hunter S. Thompson. She has received grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Kentucky Foundation for Women, and the Kentucky Arts Council. She worked at the independent, literary press, Sarabande Books, for ten years, and she was the National Publicity Consultant for Arktoi Books and the Palm Beach Poetry Festival. She has taught creative writing at the University of Louisville, Bellarmine University, and at the low-residency MFA Program in Creative Writing at Murray State. Currently, she is the Editor for the Marie Alexander Series in Prose Poetry at White Pine Press and is on faculty every summer at the Sewanee Young Writers’ Conference. She is an Assistant Professor at University of Arkansas at Little Rock and lives with her wife, poet Jessica Jacobs. nickolebrown.com |

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

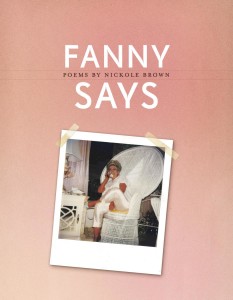

Fanny Says: A Biography in Poems, BOA Editions, 2015

Synopsis: A biography in poems of my maternal grandmother, Frances Lee Cox, from Bowling Green, Kentucky.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

For me, it’s about obsession, about having that one thing that can’t be abandoned until it’s turned over and over again, scoured free of lies and understood for what it is. It’s about the proverbial dead horse, not beaten but forensically examined so closely that the memory of that animal rises again. For me, a project book is about tenacity and involves an author Shawshanking her way through whatever impossibly thick wall with the tiny rock hammer of word and syllable, each line carrying away an ant’s load of dust. It’s not the kind of book that can be conjured on a whim; I’d even say that it’s near impossible to consciously choose an idea for a project. Instead, I feel the most successful collections of this sort arise naturally when nothing is forced and the poems that most need to live are born. These are the kind of poems that won’t let the author write anything else until they have their say; these are the kind of poems that once finished sometimes demand then to be written again until everything has been said. That’s the way it was for me when I wrote my first book, a novel-in-poems called Sister, and this second collection wouldn’t let me go until I finished either.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

Because my grandmother was as striking and contrary as rain that falls heavy while the sun is shining. Because she cussed like a soldier and wore nothing but white from head to toe and teased her hair to Jesus every morning. Because she rose up dirt poor out of Depression-era Kentucky and grew up to drive her Cadillac Eldorado down the old road—Dixie Highway—all the way to Southern Florida. Because my grandmother wouldn’t let me call her grandma but insisted I use her name. Because her name was Fanny, and there hasn’t hardly been a day in my life that I haven’t said that name. Because when my mother had me at sixteen, Fanny helped raise me. Fanny made me pick my own switch and taught me how to make cornbread in a cast iron skillet and showed me how to hold my head high and walk right past. Because her husband was a builder with a hammer-throwing temper, and still, she had seven children by him. Because her closest friend was a black woman that came to her house every day to clean it. Because no one has hardly understood me as well as Fanny did, but sometimes, I could barely understand her. I wrote this book to try to remedy that—to try to truly hear what she had to say to me, to comprehend from where she came, and ultimately, where I came from.

Are you comfortable with the term “project book”?

Sure. It’s not perfect, but it might be the best term we have, generally speaking, although I prefer to think of Fanny Says as a biography. I also worry that “project” sounds a little casual, as if it were an undertaking for the weekends, but then again I suppose the vague catch-all of “project” is necessary, especially when you consider how many different ways these sorts of collections can be linked. I mean, I’ve enjoyed project books that are novels, such as Anne Carson’s Autobiography of Red. Some other favorites are journalistic imaginings (Patricia Smith’s Blood Dazzler) or extended essays (Claudia Rankine’s Citizen, even Maggie Nelson’s Bluets) or linked fables (Rochelle Hurt’s The Rusted City). There are even historical investigations as Maurice Manning’s A Companion for Owls: Being the Commonplace Book of D. Boone, Lone Hunter, Back Woodsman, & c or Natasha Trethewey’s Bellocq’s Ophelia. These are some of the books I turn to again and again; not only to see what surprises lurk upon rereading individual poems but to investigate the connective tissue between those poems. The energy that crackles in the white space—quite literally in the turning of the page from one piece to the next—is endlessly compelling to me. It’s where the reader fills in what is unsaid and imagines what propels one poem to the next. Project books are immensely enjoyable to me. They allow for an honest portrayal of experience, especially when it comes to narratives that are fractured or not remembered in a linear way. To me, the arc in traditional novels always seems false; it’s not how I’ve known life to really be, which is often fragmented and full of memory gaps. These kinds of books allow for a story that is shattered and welcomes mystery.

Was your project defined before you started writing? To what degree did it develop organically as you added poems?

By the time I began writing this book in earnest, the raw material I needed for the collection was already drafted, really, so the years leading up to submitting the book were more about selecting, shaping, and revision than writing new work. You see, I had been writing about my grandmother—and writing down what she said—since high school. I have notebooks back to 1992 filled with her cock-eyed stories, and after I lost her in 2004, I would often write epistolaries to her. Some of these letters waded through the grief of her passing, others asked her permission or sought her advice about everything from my love life to how to make potato salad. I had to have some way to keep talking to her, so I wrote to her. That said, the development of this book was more about culling material I already had rather than creating new poems. It took about three years to shape (and reshape) what I had into the manuscript that eventually found publication, but I had been writing this work for nearly twenty years. With the exception of one poem about my marriage to Jessica Jacobs in 2013—“An Invitation for My Grandmother”—there really isn’t any work here that didn’t originate years before.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

Continuity was important to me in this collection, so naturally, the poems lean in on each other and hopefully create a sort of gestalt. But it was also essential to me that individual poems did not necessarily need each other. I think each poem is best if it’s acting as its own independent citizen, so to speak. For this reason, there was a whole bevy of poems that didn’t make the cut. In some cases, when I had weaker fragments that wouldn’t necessarily do well on their own, I quilted them together into longer, linked poems, as is the case for “Clorox” or “Pepsi” and the long sequence “A Genealogy of the Word,” which makes up the entire third section of the book. Most of the time, however, these odd little scraps had to go back into the drawer, so there were nearly fifty pages cut from the original version of this manuscript. I had to be aware of attachments I had to these weaker pieces and cut the clutter wherever I could. It was difficult to see these babies go but, even though they served the overall plot, they ultimately weakened the collection. After this was done, the sequencing of these pieces was an important part of the book’s architecture as well. I can’t tell you how long I sat on the floor, shifting pages from one end of the room to the other, trying to find the exact order for these poems. My cats had great fun rolling in the pages, trying to help in their way too.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

Full immersion always works best for me. I’m a highly distractible thing, and worse yet, I tend to fidget and spook when I get to particularly difficult material. If I were a horse, you’d find I run much better with my blinders on, cupping my eyes from seeing anything other than what I need to see to move forward. Sometimes, other poems did come while writing this book, but generally speaking, those pieces were mere procrastination, pieces that I wrote to distract me from the uncomfortable material I needed to face. I would sometimes limber up with funky wordplay or highly associative numbers that refreshed me in some way, but most of the time, this produced less complicated and challenging material.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

Well, I’m currently in that limbo, so I don’t know if I can accurately speak of how to best transition into something new, but yes, I do have another project in the oven cooking very slowly. Casually called my “green tab” poems because of the green Post-it tabs I used to mark the relevant material for this project in my notebooks, these poems are about something I’m just beginning to articulate: how I’ve come, finally, at this late stage in my life, to live in my body. I mean, there were many ways in which the childhood I had not only turned me towards books but turned me into a book, into a girl made of ink and syllables instead of blood and breath. I’ve lived that way for years, fairly sedentary, avoiding physical experiences. For example, quite literally I never jogged anywhere until two years ago when my wife convinced me to huff around the block. It extended my lungs to burning and jolted my heart awake; it hurt like hell and made me feel deeply ashamed of how I’d neglected this body that had carried me thus far. I imagine this new manuscript will be a memoir of sorts, but I want it to be deeply focused on the physical body, to be a poetry of the body in all its embarrassing, ecstatic sensations. I’ve been paying attention, taking notes. I’ve also been researching by reading a number of endlessly fascinating, macabre books about human anatomy and physical illness. I’m a slow writer, hesitant to put anything into the world until I’ve sat on it a good, long while, so this might take me years to quite literally flesh out. We’ll see what happens.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

Most importantly, don’t force it. And don’t define your guiding principles until they arrive naturally. I often see students cook up a project idea that sounds cool only to find it to be something they can’t sustain on their own or one that doesn’t offer up material that is compelling after a few months’ work. Make sure to lean into your obsessions, whatever they are, and don’t question if what compels you fits your idea of a manuscript. Let your creative self speak first, before you concern yourself with marketing or the feasibility of the book. I think this is especially important. If you find yourself writing what you think will sell, you might end up with a trendy but ultimately thin work. I’d also recommend a deep study of other genres. My time studying fiction at Vermont College has been tremendously helpful for me as a poet writing out extended narratives in my verse, and this summer, I plan to spend time looking closely into works of creative nonfiction for some ideas of how to enter into this next project.