BETTINA JUDD is an interdisciplinary writer, artist and performer. She is an alumna of Spelman College and the University of Maryland and is currently Visiting Assistant Professor of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies at the College of William and Mary. She has received fellowships from the Five Colleges, The Vermont Studio Center and the University of Maryland. She is a Cave Canem Fellow and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize in poetry. Her poems have appeared in Torch, Mythium, Meridians and other journals and anthologies. Patient. won the Black Lawrence Press Hudson Book Prize. As a singer, she has been invited to perform for audiences in Vancouver, Washington, DC, Atlanta, Paris, New York, and Mumbai. [Photo credit: Rachel Eliza Griffiths] BETTINA JUDD is an interdisciplinary writer, artist and performer. She is an alumna of Spelman College and the University of Maryland and is currently Visiting Assistant Professor of Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies at the College of William and Mary. She has received fellowships from the Five Colleges, The Vermont Studio Center and the University of Maryland. She is a Cave Canem Fellow and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize in poetry. Her poems have appeared in Torch, Mythium, Meridians and other journals and anthologies. Patient. won the Black Lawrence Press Hudson Book Prize. As a singer, she has been invited to perform for audiences in Vancouver, Washington, DC, Atlanta, Paris, New York, and Mumbai. [Photo credit: Rachel Eliza Griffiths] |

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

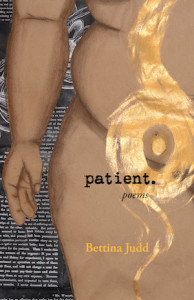

patient., Black Lawrence Press, 2014

Synopsis: Poems connecting the legacy of medical experimentation on Black women during slavery to practices in present day.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

It focuses on a set of related themes and extends beyond the binding of the book itself.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

There is a compelling lesser-known history in exploring the legacies of Anarcha Wescott, Betsey Harris, Lucy Zimmerman, Henrietta Lacks, Joice Heth, and others that tells us something about how Black women’s suffering is at the foundation of our culture: from the wet-nursing of so-called founding fathers, to medical advances, to popular entertainment. While there is this sordid history of slavery from which we cultivated attitudes about race, as a culture we continue to devalue Black women’s pain. We render it neutral or invisible through stereotype and mockery. Consider the stereotype of the “angry black woman” and how that silences and mischaracterizes us repeatedly. We become a meme, or a symbol of long suffering. Empathy is harder to come by when this is our cultural status quo. The founding of these medical practices, however, affect all women. But we don’t know it, and when we know it, we have difficulty registering the pain involved in it. Without such empathy I doubt our ability to attest to our own humanity.

Are you comfortable with the term “project book”?

I suppose. It is a project. The book is a major part of it. There are more components. I want women of color to tell their stories. I want teachers to share resources on this history.

Was your project defined before you started writing? To what degree did it develop organically as you added poems?

The project was a project first. It was a series of paintings. Then it became poems. At the onset of writing poems, I knew there would be many poems but I was not sure that they would result in a book of poetry.

Did you allow yourself to break your own rules?

I didn’t have any rules, really. I did want it to be more visual. That component exists, but I never made any rules about it.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

It was relatively important that the poems stood on their own. Many of them serve as connective tissue to a narrative, but even those poems took up concepts of connectivity that matter on their own. The major challenge with this is that I wanted to be able to tell the story without enforcing a singular narrative—allowing for the messiness of history. I intended to rely on references to compel the reader to look up this history on their own. This didn’t work so eventually I did sit down to pen poems that specifically told the history in a narrative fashion, but those poems wound up telling the greater story of the project—that the past haunts the present.

At any point did you feel you were including (or were tempted to include) weaker poems in service of the project’s overall needs? This is a risk, and a common critique, of many project books. How did you deal with this?

Some of my attempts to serve the project’s overall needs wound up being the stronger poems because they propelled the project forward and forced me to consider why I was writing the poems in the first place. These poems were a place for the overarching narrative voice to question its own existence, its motivations. There may be some weaker poems. I’ll leave that to reviewers.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

When I find an obsession, I pretty much stick with it. This does not mean that I do not work on other projects, but that some of the elements I am concerned with exist in these other projects as well. I enjoy writing poetry, so of course poems with other themes were written during the course of this project, but I was also working on a dissertation in Women’s Studies. That dissertation was not about the history of gynecology or medical experimentation and display of enslaved women. The dissertation project I was working on was about Black feminist thought and Black women’s creative production. The tethers are there. I was dissertating a defense of patient.

Did you ever lose momentum, bore yourself, or worry that your project could not be sustained for a full-length book? How did you push through?

I thought that I could not get through the poems about Anarcha, Betsey, and Lucy because J. Marion Sims’ shadow loomed so large over their stories. I wanted to pull more truth from the women and I wanted to be true to the history as well. This is difficult for giving voice to any of the enslaved. It is the function of slavery that disallows for their stories to be heard. So I had to put my own sense of heartbreak into the small things I could learn about them through Sims. For example, Betsey was described as the youngest of the three initial women who were experimented on by Sims. She was also formally enslaved by a medical doctor and was described as having just been married. There is a story in that already. How does an enslaved woman really get to be married in the 19th century when they are already considered property? What did Betsey see as someone who was enslaved by a doctor? What might she have known already before her time with Sims? Perhaps the poems could attempt to answer these questions, flesh her story out and add to the project overall.

As you were writing, were you influenced by your experience or perception of how project books are received by readers and editors (either positively or negatively)? Do you feel differently about your book being defined as a “project book” now that it has been published than you did when you were writing it?

I greatly admire book projects. I am very influenced by Natasha Trethewey and Claudia Rankine, whose collections may settle deeply into a topic. I like that kind of depth to my experience as a reader and didn’t really have a sense of it as a negative for poetry. It helped that as I was crafting these poems, I was also sharing them and found that there was a community of women who needed to hear them. They had experiences with doctors and this history and the way that I was connecting it to the present resonated with them. I didn’t know if the project would be successful monetarily, but I knew the project had meaning with a particular audience and I was honored by that connection.

Do you have a sense of whether the fact that this is a project book helped position it to find publication more easily? Has it helped you find readers?

It won The Hudson Book Award. That is how it was published. I do think people interested in the subject and not necessarily poetry have picked up the book. I don’t know about the other way around.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

I’m working on turning that dissertation into a book. There are other tiny obsessions in little folders. I will get to them as they, too, haunt me.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

Find the greater truth in your project. Interrogate and question your intentions and assumptions. Go to the place that is most vulnerable for you as an “expert” on the subject. Write from there.