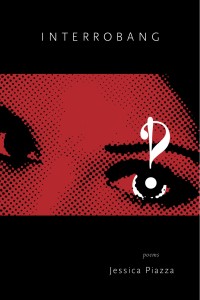

JESSICA PIAZZA is the author of two full-length poetry collections from Red Hen Press: Interrobang — winner of the AROHO 2011 To the Lighthouse Poetry Prize and the 2013 Balcones Poetry Prize — and Obliterations (with Heather Aimee O’Neill, forthcoming), as well as the chapbook This is not a sky (Black Lawrence Press). She holds a Ph.D. in English Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Southern California, is a co-founder of Bat City Review and Gold Line Press, and teaches for the Writing Program at USC and the online MFA program at the University of Arkansas at Monticello. In 2015 she started the “Poetry Has Value” project, hoping to spark conversations about poetry and worth. Learn more at www.jessicapiazza.com or poetryhasvalue.com. JESSICA PIAZZA is the author of two full-length poetry collections from Red Hen Press: Interrobang — winner of the AROHO 2011 To the Lighthouse Poetry Prize and the 2013 Balcones Poetry Prize — and Obliterations (with Heather Aimee O’Neill, forthcoming), as well as the chapbook This is not a sky (Black Lawrence Press). She holds a Ph.D. in English Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Southern California, is a co-founder of Bat City Review and Gold Line Press, and teaches for the Writing Program at USC and the online MFA program at the University of Arkansas at Monticello. In 2015 she started the “Poetry Has Value” project, hoping to spark conversations about poetry and worth. Learn more at www.jessicapiazza.com or poetryhasvalue.com. |

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Interrobang, Red Hen Press, 2013

Synopsis: Interrobang is a collection of formal poems (primarily sonnets) titled after clinical phobias and clinical philias.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

Since all but three of the poems are titled after phobias and philias, it pretty much fits the bill right off the bat. The fact that the collection is primarily formal poems also compounds the project feeling.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

Fears. Lusts. Those are the things that drive us. Those are the real subjects, the big ones, and I find them fascinating. The fact that clinical phobias and philias are a sort of exaggerated version of those, well, it fascinated me. Researching them I kept thinking these pathologies weren’t that far off regular fears and loves we all have but, like a rubber band stretched too far and too much, they couldn’t hold proper shape anymore. They didn’t fit society’s notions of useful, so they had to be discarded (or hidden away.)

Was your project defined before you started writing? To what degree did it develop organically as you added poems?

It definitely wasn’t defined. In fact, the whole thing started because I had a panic attack when I tried to go spelunking. I bailed, got home and started trying to figure out what my apparent newly minted phobia was. It wasn’t claustrophobia, though that’s what everyone tried to tell me, because it wasn’t the small space that bothered me. (I eventually learned it is actually a version of agoraphobia. The term is commonly used for people who won’t leave the house, but actually it’s a fear of not having easy means of escape.) Anyway, that phobia research was consuming, and I started to realize that so many of my poems—especially the ones that had felt a little off and I couldn’t put my finger on when it came to revisions—really hinged upon these same questions. I went over some of my unfinished work, and there was a recurring thematic footprint: huge fears and our innate need to hide them in order to seem like we conform. Once I added the philias to the project, which was a natural progression in my research of phobias, everything fell into place. I wrote many new poems, but also had an organizing and editing principle for that older work that hadn’t previously shined.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

As I’ll mention over and over, obsession is my favorite writing partner. When I was doing this, I didn’t do anything else poetically. I’m all in. I’m just that type of person.

As you were writing, were you influenced by your experience or perception of how project books are received by readers and editors (either positively or negatively)? Do you feel differently about your book being defined as a “project book” now that it has been published than you did when you were writing it?

I think editors lately appreciate a project book, but I had a few things working against me going the contest route. My book is both a very specific project and comprised of formal poems. I am heavily into music, internal rhymes and language play, but these poems are about going over the top and then some, so I’m not afraid to swear or be blunt with my language or subject matter. There’s a lot of sex. In a way, I think I was too edgy for the formalists and too formal for the more experimental publishers. That being said, people were pretty receptive to the subject matter itself, so I’m going to guess that helped. But it certainly got rejected enough times! Like so many of us, I had to believe that this project, this gimmick, was worth it. And that if it wasn’t it didn’t matter because it was my obsession, and that’s just how it is. It’s funny, though – the book came close at a lot of presses before it was taken, but wasn’t taken for a few years. I think after I published it the same things that turned publishers away from it (the prosody, the sex, etc.) is what has drawn readers to it.

As a reader, are you drawn to project books? What project books have influenced you or have you enjoyed, and what do you think makes those books successful?

I’m absolutely drawn to project books. I’m really obsessed with obsession itself, and project books at their best are a rigorous manifestation of a poetic obsession. I wrote Interrobang because I became fascinated with these clinical fears (and eventually with the lusts, too) and I just couldn’t stop thinking about it; how there were so many seemingly innocent things that could trigger terrible, awesome reactions in people. When you can’t stop thinking about something it becomes a part of you, and I think that’s what brings amazing project books together so well. Not just that there are themes, but that you can feel the necessity of the writing in a way you often can’t in more loosely tied together collections.

Have you abandoned other project attempts? How did you know it was time to let go? What happens to project poems that never amass a full-length book?

Oh yes. At this point in my life I pretty much only write in projects, so I’ve abandoned a bunch. The hope is that a subject I admire will make it far enough to create a chapbook. That’s what happened with my latest chapbook, This is not a sky (Black Lawrence Press). It’s a collection of ekphrastic poems. I got very excited about this idea of writing about the paintings in an almost straightforward way, but then having this italicized voice run through the collection as a kind of instigator or foil to the rest of the writing. I was lucky enough that it held interest for me long enough to be chapbook-length, but I was definitely done when I was done. Other projects I’ve started, though – poems on different types of bridges (which I’m so into), for example, and a collection using the military alphabet as a springboard – those haven’t come to anything. Yet. I always like to say yet, but who knows.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

Always another project. Just not sure which one will stick yet. Just wish me luck.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

Don’t be afraid of the word gimmicky. You hear it a lot in poetry workshops, but I think the most interesting work in almost every era takes on a challenge of structure, form or content that someone could call a gimmick. So own it, but be careful of a few things. Poems that fit a theme but can’t stand on their own are problematic for a lot of reasons, chief among them that many people don’t read books all the way through or all at once. Also, a tight theme can be generative in so many ways, but when writing toward a theme poets sometimes find themselves writing poems that are too similar (in voice, narrative, content) without breath or breadth or variety of approach. No one wants to read the same thing over and over again, so write a million poems on a theme if you want, but ultimately cull them to make sure that each brings something wonderful and individual to the idea. And don’t stretch poems too much to accommodate a theme. The project might generate some writing that doesn’t ultimately fit; you can always use that later.