Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

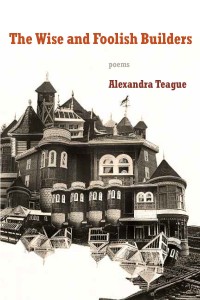

The Wise and Foolish Builders, Persea Books, April 2015

Synopsis: Building out from the story of Sarah Winchester, Victorian heiress to the rifle fortune, and the large, strange house she constructed in California, supposedly to appease the ghosts of everyone killed with Winchester rifles, The Wise and Foolish Builders explores the intertwined facts and legends, and ongoing legacies, of “The Gun that Won the West” and Westward expansion.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

I see project books as having a fairly cohesive or identifiable central theme and/or form; in my case, Sarah Winchester’s story returns throughout, and many of the other poems—e.g. a series of “Ghost Tour” poems or poems about the repeating rifles—directly relate to her. My book is also very concerned with a range of formal constructions to explore how we construct our understandings of this history and its figures. But I imagine most project books are like most poems: they don’t hew entirely to their original impulse/conception. With The Wise and Foolish Builders, I certainly ended up writing poems about a lot of what I originally imagined—the architecture of the house, the repeating rifles, various ghosts, for instance—but the research and my own preoccupations, as well as subjects I never found a way to write about, took the book in so many directions I couldn’t have anticipated. So I think of it as a project book—with a lot of emphasis on the active-construction, process aspects of “project.”

Why this subject (or constraint)?

Sarah Winchester originally interested me because of the standard legend about her: that she was told she had to eternally build to appease the ghosts of everyone killed with Winchester rifles. I grew up in a maybe haunted house, have lost people close to me, and moved West as an adult, and gun violence is a subject that concerns me, and which I’ve taught about over the years—so there are personal resonances. Initially, I imagined a series of poems—something that would launch me in a different direction than my more autobiographical first book. Once I started researching, I became fascinated with so many other aspects of this history, as well as the language in the historical sources. And while I quickly came to see the ghost story about Sarah as an advertising legend, I also saw it as speaking to collective guilt over the role of “The Gun That Won the West” and this country’s unsettled relationship to that history and to Manifest Destiny. I’m also really struck by the fact that Sarah, as an unconventional, brilliant widow, was said to carry this guilt, despite having no direct involvement in manufacturing the guns. So the book became about retelling her story in a more layered and formally varied way than it’s usually presented, and with other women’s voices, and more personal voices from the present and history.

Did you allow yourself to break your own rules?

Definitely. For instance, I surprised myself by writing a poem in which Sarah Winchester, 46 years dead, talks to Andy Warhol, which led to a number of other poems that play with anachronistic conversations to get at layered understandings of history and the legacies of Sarah’s story (and the idea of ghosts within it)—and that allow her to say things that might not have been expressible in her own time period. I originally planned to write more contemporary gun violence poems, and did write some, but felt they were finally less interesting than the historical and anachronistic lenses on this subject. And I really wanted to write a poem about the Plains Indian Ghost Dance, but never found a way to that didn’t feel in some ways culturally appropriative. Finally I had to let the book be the idiosyncratic construction it was—given who I am/was as I was writing, and the research I did, and stories I found most resonant, though I stuck to some original concepts very closely, e.g. having a villanelle called “Repeater” about the guns, which was one of my first ideas and one of the last poems I actually figured out how to write.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

This was very important to me, and something I struggled with. On a practical level, a continual challenge was titling the poems so that every single poem didn’t have to repeat the Winchester context to make sense. And then I ran into problems of having written too many poems that explored similar themes; as I was trying to put together the manuscript, I realized that I’d re-covered a lot of the same ground, which had been less evident when the poems were being published separately. I also really struggled—in a way that eventually started to seem like Sarah’s legendary curse of eternal building—with structuring the book. I think my editor had to deal with about 8 different versions over the two years between acceptance and publication. Much of that had to do with finding ways to maintain the narrative threads without feeling obligated to tell a chronological story of Sarah’s life or Westward expansion—to find ways of moving among times and places and voices and creating interesting frictions, but also overlaps and enough cohesiveness to orient the reader.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

I worked on this book for about five years, and I wrote a lot of non-Winchester poems along the way; in one sense, this felt like cheating on the concept and the copious notes I’d taken on research trips to San Jose and to the Buffalo Bill Historical Center’s McCracken Research Library. But I also felt as if I would deaden/weaken my poems, and my ability to really live into my relationship with this material, if I was always just trying to write what I should. And sometimes I just really didn’t have anything to say about this material, or was excited about something else. I think these phases of backing away and/or wrestling with why and how the Winchester material mattered to me were really essential. And in some cases the “non-Winchester” poems ended up in the book because I realized later that they really were in conversation with the central material.

Ironically (or maybe naturally), many of the other non-Winchester poems have become the start of my next book, which is a slightly less cohesive project about nudity and statues and artists’ models and things that might seem to be entirely different from The Wise and Foolish Builders, but also come out of some concerns and ideas I developed while writing it.

As a reader, are you drawn to project books? What project books have influenced you or have you enjoyed, and what do you think makes those books successful?

Yes, I became really interested as I was completing my first book (which was written sporadically over about 14 years and was certainly not a project book) with a number of contemporary books that refigure history and create really fascinating, layered voicings—e.g. Tyehimba Jess’s Leadbelly or Gabrielle Calvocoressi’s The Last Time I Saw Amelia Earhart, or Elizabeth Bradfield’s Approaching Ice. Part of what drew me to Calvocoressi’s and Bradfield’s books was the interplay between the personal poems and the researched history—the complex conversations that could occur there. I think poetry—with its formal capacities and also the possibility of a single book holding so many different voices and angles—is particularly wonderfully suited for these sorts of investigations of history and its ongoing resonances.

As a teacher, how do you see the prevalence of project books and other poetic constraints affecting your students’ writing?

I definitely have a number of MFA students who are much more worried than I was, in the 90s, about having a cohesive project. I tell them that we tend to gravitate toward our own preoccupations, so any thesis is going to be cohesive enough to have conversations among its parts—and I also think it’s crucial to keep challenging ourselves to write in new directions. So I try to be open to the cohesive project that a student feels drawn to, but also not to make them feel as if that’s necessary. That said, I’ve had some students write some fantastic project theses, and be really inspired by the constraint of the theme and/or form.

I went to University of Florida for my MFA, and several of my professors, including the wonderful William Logan, gave us poetic constraints each week—e.g. write a poem in iambic pentameter with a butterfly in line four and no more than one color name and . . . I learned so much about how to creatively work within constraints—what the Tang Dynasty writer Han Yu called, in reference to writing in form, “the dance in chains.” I likewise have my students work within various constraints: this semester, each week, they’re writing an elegy or ode or pastoral or ekphrasis or other poetic mode/genre, after we’ve discussed the tradition. I see students recognizing that they’re actually more creative when they give themselves (or someone gives them) certain strictures. I think a project is just one means of exploring how we can surprise ourselves because of / despite constraints.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

I’ve already said a lot of it: keep questioning and deepening your relationship to your original conception, but also don’t try to keep the project in a bell jar. I spent most of my four years of main writing thinking that I was doing something very different from my first, more autobiographical book, and didn’t realize until I’d completed The Wise and Foolish Builders the ways in which it’s a natural outgrowth of that material, and still extremely personal. I’d invoke Adrienne Rich’s idea that “Poems are like dreams: in them you put what you don’t know you know,” and say that a good project is wonderfully like this too.