Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

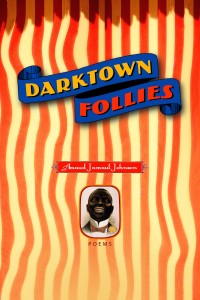

Darktown Follies, Tupelo Press, 2013

Synopsis: This collection responds to the history of Black Vaudeville, specifically the concerns of African American entertainers performing in blackface in the early 20th Century.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

For better or worse, I believe our obsessions define us. There isn’t anything particularly unique about “falling in love” with a subject, except the impulse to dissect/compartmentalize our fascinations. I don’t knit or garden or paint; I write poems, so my obsessions are exposed/managed/contained in the pages of this collection. Before I knew I was a poet, I knew I spent far too much time “considering” fairly obscure details of any given subject. “Yet do I marvel at this curious thing.” Darktown Follies might be considered a “project book” because it hovers around a central question. I began asking what it means for humor to fail. I began questioning the vulnerability or viciousness behind telling jokes. As poets, of course, our relationship to intentionality can be murky. What we want and what the poem requires are often very different. While writing, I hope to feel surprised and sometimes lost. This book is very different from what I initially imagined; however, I imagined it would take unexpected turns. The poem’s “shadow subject” and “physical counterpart” do a strange dance.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

I heard Billy Collins read a few years ago. It was at Stanford, before a crowd of a few hundred. People seemed completely entertained, and at the conclusion of the reading, Collins took questions. The first person to approach the microphone asked: “Do you consider yourself a clown?” Now, I’m not foolish enough to say anything negative about Billy Collins, Oprah, or the NRA, but let’s just say at that moment I began working on this book. Mostly, I started questioning the fragility of humor.

Are you comfortable with the term “project book”?

Growing up in Compton, the two nearest housing projects were Jordan Downs and Imperial Gardens. Turning into the PJs didn’t necessarily mean death outright, but outsiders were obvious, and the inner streets all seemed to run into cul-de-sacs. You couldn’t navigate on instinct alone, so getting out of the PJs required calm and sometimes “serious” negotiation. A “project book” can present the same dangers for poetry: a place where poems are trapped or confined. While comfort/pleasure is possible, “projects” are places one “ends up” or “passes through” or “skirts,” they are “involuntary,” they are places “greyed in and grey.” So, no: I’m not comfortable with the term.

Did you allow yourself to break your own rules?

From the beginning, I imagined these poems as an act of self-sabotage. I wanted to pull apart my aesthetic. If we’ve gained from art-making over the last half century, from Blakey to Basquiat, bending and breaking have become the standard. In writing both Red Summer and Darktown Follies, there were poems that didn’t seem to work, that didn’t fit, poems about domestic abuse or romance, poems that were personal. This movement between the historical and the personal represents risk for me. Regardless of how I’m judged, I have to trust where my obsessions lead. Changing rules midway through a game is called cheating, but this isn’t a game.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

A poem isn’t a poem if it can’t stand alone. However, language doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Even if the human condition is loneliness, voices and bodies surround us. That said, I write with two different readers in mind. Personally, I rarely read a poetry collection in sequence, cover to cover. I find pleasure in moving between several books, selecting poems at random. I want to stumble onto treasures, and assume that I’m missing greater works, which pulls me back into a collection. Of course, I understand that many read books conventionally, so I organize my writing with both experiences in mind.

Did you ever lose momentum, bore yourself, or worry that your project could not be sustained for a full-length book? How did you push through?

Some obsessions yield real results: a poem, a series, a section, or an entire manuscript. Sometimes an obsession represents a period in one’s writing life or an entire career. Momentum is about time and perspective. I do fall out of love with some subjects, but I’m always questioning whether this represents frustration or just laziness. I played a really bad round of golf four years ago, and I haven’t picked up my clubs since. Now, I didn’t quit playing, but I’m not in a rush to revisit that hurt. In a few years, if I win The Masters, this will be a footnote in my epic journey. My real gift is patience. I don’t bore easily, nor am I easily excited. I’ve never been in a hurry. Failure and faith are measured through time. I don’t worry much about “pushing through.”

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

When I finished Red Summer, I told myself “I’m just going to write poems.” I sat at my desk, drank coffee, stared out my window, thought about my childhood, about politics, the media, about landscapes, flowers. Nothing came. I’ve always enjoyed history, so when I began reading old joke books, and flipping through photographs from the vaudeville era, something clicked, a flood of voices and images overtook me. I found myself immersed in a new world, and after a few years I had a draft of what would become Darktown Follies. My new work concerns articulations of romance and failure within Black urban communities of the early 1970s. I’m fascinated with the concept of the “post-soul” in reimagining the generational shift after the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements. My research includes music, film, and science fiction. It’s ambitious and wide open.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

Try not to fear what moves you. You don’t have to theorize what you love. The poems are an invocation, a framework, not the final word.