Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

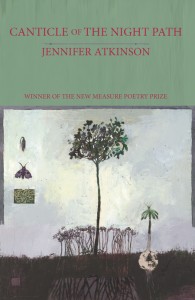

Canticle of the Night Path, Parlor Press/ Free Verse Editions, 2012

Synopsis: If I can’t do this, does it mean I haven’t written a “project book”? Here’s a sentence from the press release: “The poems in Jennifer Atkinson’s Canticle of the Night Path, collected in alphabetical order from “Canticle of A” to “Canticle of Zed,” are little songs of five—five lines, five sentences, five couplets, or five paragraphs—canticles to, for, with, and of all sorts of things.”

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

If my own is a project, then I’d say a project book is one with a coherence beyond likeness of tone and sensibility. Perhaps it’s a book that can be described (more or less accurately) in a single sentence.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

I wrote the first canticle in Assisi, where I’d gone to see the Giotto frescoes. I had reservations for 3 nights at a convent right in town. I had no particular plan, but my room was wonderful—a chaste twin bed, an armoire, and a desk under a window that looked out on the convent garden. It was almost spring, raw and foggy, and the cypresses outside struck me as the solemnest trees I’d ever seen. The room was ideal for writing, but if the airline hadn’t lost my luggage and refused to bring it up the mountain to me in Assisi, I probably would have spent very little time there. As it was, I had no coat for the February cold and I had to hand wash my clothes and dry them each night. Convented and cloistered until they dried, I read about Assisi and the frescoes and the town’s famous alums, Sts. Francis and Clare. I re-read Francis’s famous “Canticle” (one of the first poems to be written and preserved in demotic Italian) and thought about cypresses, Giotto, saintness, and what “canticle” might mean.

Little song. Nothing so grand and epic as a canto! Canticle struck me as the perfect word for the lyric poem I wanted to write. At the same time I had been re-experimenting with variations on the ghazal form. (My previous book, The Drowned City, concludes with several ghazal experiments, and I just couldn’t stop noodling around with the form.) That’s where the first canticle came from, then: Assisi, little song (with a nod to Francis’s praise song), and the ghazal’s minimum number of couplets: 5.

I didn’t know “Canticle of the Rain” would be part of a series, never mind a book-length project: I wrote lines at my little convent desk, lines that found their form in a poem. A single poem. Months later, during which time I was writing occasional eco-ish landscape poems, I got to thinking again about canticles. By then, I’d started reading Mary Magdalene legends, the subject of one of Giotto’s lyric-narrative sequences in Assisi. I loved the stories, of course—full, as they are, of magic and nakedness and questions about the sacred—and I became rather obsessed, I’ll admit, seeking out every image and legend I could. Maybe it was inevitable that MM, the author whose damaged-to-fragments gospel (gapped at heart-breaking moments like a Sappho papyrus!) had grabbed me years before when I came upon it in the Nag Hammadi texts, would find the canticle form so amicable?

The obsession led me to the epicenter of Magdalenean legends—Provence, where I wrote 30 more canticles in 30 days. If it weren’t for that rush of poems—all revised a lot afterwards, of course—the book wouldn’t feel like a “project,” I don’t think, despite the formal 5 thread that runs throughout. The homagey poems for various French and Italian poets (and Hopkins) might seem too unlike the ones about Magdalene or the prose ones called Magdalene’s parables or the ones in praise of clouds or a crow. Really Canticle of the Night Path is several “project” strands woven together, balanced formally, trying to find a wholeness in what Elizabeth Bishop called in Calder’s work “composed motions.”

Are you comfortable with the term “project book”?

Not altogether, since it sounds so premeditated and willed into existence—dutiful. I like the term “book-length sequence” better for my work and process.

Did you allow yourself to break your own rules?

Absolutely. But I did keep to the 5—in revision if not in first writing.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed?

In my case, it was crucial for every poem to be self-supporting and whole on its own, unchaperoned. But I’ll concede that other “project” books might need frame poems or transitions…

At any point did you feel you were including (or were tempted to include) weaker poems in service of the project’s overall needs? This is a risk, and a common critique, of many project books. How did you deal with this?

Not a problem for me. I wrote at least a dozen other canticles that didn’t make the cut. The only one I wrote for the book was “Canticle of Zed.” A friend said it wasn’t fully satisfying without a Z. She was right, as always, so I had an assignment. Funny, but I treated that like a prompt, which I love. For the space of one poem, I love a “project.” I guess I have to admit that having some sort of plan encourages a quick start in the morning.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

I did work on other things. Those eco-meditations I mentioned earlier continued. Even during the 30-day rush, I worked on them in the afternoons, but only after exhausting my good morning energy on the canticles.

Did you ever lose momentum, bore yourself, or worry that your project could not be sustained for a full-length book?

I would have worried that, if I’d intended all along to write the book I did. Probably, if I’d started with an outline and told myself I had to fill in that outline, I’d have drifted off instantly (if drifting can be instantaneous). Maybe the outline would have turned into a poem and that would have been that.

Do you have a sense of whether the fact that this is a project book helped position it to find publication more easily? Has it helped you find readers?

Maybe. I do think the way the book can be described succinctly has made it more amenable to reviews. It’s hard to tell.

As a teacher, how do you see the prevalence of project books and other poetic constraints affecting your students’ writing?

I’m not sure about what influence the “project” book has had on poetry in general, but I have noticed that students more often feel the need to define a project before they enter into the thesis process. For some, the constraint works to focus their efforts. For others, the project bogs them down and distracts them from composing lines and poems. I try to encourage them to discover their project within the work they have already written and feel good about. What are they already working toward? What are their strengths and interests already?

Have you abandoned other project attempts? How did you know it was time to let go? What happens to project poems that never amass a full-length book?

I abandoned one a while back when I realized I wasn’t compelled to write another poem toward it. The several I had written folded into the eco-ish bunch I’d been writing “on the side” for so long. There was one I sustained a bit longer, but it was like wrestling an alligator without the toothy danger. Maybe I’ll return to the idea someday, so superstitious as I am, I will not mention it here.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

Out of a longtime love and fascination with Agnes Martin, I’ve started a “projecty” bunch of poems on painterly abstraction. Not sure where it’s going, but I’ve written about 30 poems…

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

Don’t bore yourself. Poetry asks of us both industry and idleness, drift and direction.