Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

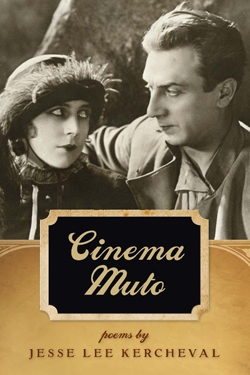

Cinema Muto, Southern Illinois University Press, 2009

Synopsis: Cinema Muto is a book of poems about the lost world of silent film, the silent film festival Le Giornate del Cinema Muto held every October north of Venice, and the ephemeral nature of film, life, and love.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

Obsession.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

It was involuntary, as all true obsessions are. I thought I was going to a silent film festival because it was A) in Italy, and B) my husband asked me to go with him. I ended up going back year after year and writing over the statutory limit of poems about silent movies—far more than are in the book. I could not stop myself.

Was your project defined before you started writing? To what degree did it develop organically as you added poems?

It started as a surprise, then grew into a larger and larger project. In October, 2001, I went to the Le Giornate del Cinema Muto for the first time thinking I would sit in a cafe and drink espresso and write poems (not about silent movies) while my husband sat in the dark and watched the films. Instead, I fell madly in love with silent film as a lost art and refused to leave the theater if there was a movie playing (and at Le Giornate, they screen movies from 9 am until 1 am almost without pause for 8 days, so that is a serious commitment).

Then after the festival, I started writing poems about the films I had seen and the themes that seemed to link them. At first I thought, Oh look, a batch of poems about silent films. Then, Oh maybe I am writing a chapbook about silent film. But I kept writing poems. Then I knew I wanted a book of poems that mirrored one year at the festival—arriving, sinking into this lost world, seeing films until you begin to hallucinate, leaving, returning to the real world. But it took me more festivals and more years than one to write the book I wanted—so in the end, I shaped five years of festivals into one arc, into one imaginary, very full festival week.

Did you allow yourself to break your own rules?

There are some poems that are not explicitly about silent films, but rather about being in Italy or with my husband. However, they are still about the experience of being at Le Giornate. They came out organically, as part of the project, so I am not sure I perceived them as breaking the rules. One “rule” which I violated early and often is that most of the poems start with a quotation from the catalogue for that year’s festival, saying something about the film, or the director, that helps set up the poem. But if I didn’t feel the poem needed that, I omitted it.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

At first, it was important to me that the poems all stood on their own. But as I went along, I wrote some odder ones or littler ones that I saw as serving as connecting tissue and not as standing alone. But, in the end, I think all of the poems in the book did appear in magazines—so perhaps I was wrong!

At any point did you feel you were including (or were tempted to include) weaker poems in service of the project’s overall needs? This is a risk, and a common critique, of many project books. How did you deal with this?

My biggest problem was that I often wrote more than one poem about a single movie, especially one that really impressed me (Abel Gance’s six-hour silent epic Napoleon), but in the end, I felt that didn’t work. I had to choose between the poems, sometimes based on strength of the poem, sometimes based on what the book needed. I also found I had poems about different movies that were really meditations on the same theme and so had to cut poems for that reason as well. Also, I wrote nearly twice as many poems than I could include, so I had to cut some!

I think a poem is often stronger in the context of a collection—and not just in a project book. So I don’t agree with the idea that this is an inherent weakness of having a project at the heart of your book. If a project book seems thin, I would suggest the author should have written more poems, worked on it longer. And I think that critique holds for any book of poems.

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

I am afraid I am someone who is always working on more than one book—though usually in different genres (poetry and fiction or nonfiction or translation). While working on Cinema Muto, I was also writing my novel My Life as a Silent Movie, a sure sign of the size of my obsession with silent film!

Did you ever lose momentum, bore yourself, or worry that your project could not be sustained for a full-length book? How did you push through?

I was too obsessed to be bored, but I wondered if anyone else would be interested in reading the book when I finished it! I was aware I was combining two fairly obscure obsessions—silent movies and poetry. I thought Cinema Muto probably had an audience of one—and I was it! But the acceptances from lovely magazine editors gave me hope that was not the case. Also, as I said, I was obsessed, so the poet in me would not take any sensible suggestions from the editor in me to write something else.

As you were writing, were you influenced by your experience or perception of how project books are received by readers and editors (either positively or negatively)? Do you feel differently about your book being defined as a “project book” now that it has been published than you did when you were writing it?

I think I had the vague idea that as a poet you “grow up” and write a project book—though I had not heard that term at the time. The way fiction writers often believe you write a book of stories first, then you are ready to try a novel. I thought I would work on a “project” after my first book, World as Dictionary. I tried various projects on for size, all rather artificial (a poem a day, etc.), but none worked. My second book, Dog Angel, was not written as a project. Then I went to Italy and into a dark theater where they were screening an obscure, nearly completely forgotten silent movie—and, bam, I started work on Cinema Muto.

Do you have a sense of whether the fact that this is a project book helped position it to find publication more easily? Has it helped you find readers?

Honestly, I think the fact Cinema Muto was a project book made it more difficult. The editor of a previous book wrote me a note that said, basically, Any book but this one. So, though the individual poems were actually easy to place in magazines, the book was more difficult to publish. But, in the end, David Wojahn picked it for the Crab Orchard Open Selection Award, and SIU Press did a gorgeous design for it.

After completing a project, how did you transition into writing something new? What are you working on now? Another project?

I moved on to another obsession or a series of them—in this case learning Spanish, translating Uruguayan poetry, and writing poems in Spanish. My long poem in Spanish, Torres, was just published as a chapbook in Uruguay by Editorial Yaugurú. A full-length collection of my Spanish poems, Extranjera, will be published by the same press in May, 2015.

My translations, which are very much feeding my own poetry right now, have led to two forthcoming books: Invisible Bridge: Selected Poems of Circe Maia, a collection of the Uruguayan poet Circe Maia’s poems that I selected and translated, which will be published the University of Pittsburgh Press, and América invertida: a bilingual anthology of younger Uruguayan poets, an anthology I edited, which will be published by the University of New Mexico Press.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

I will offer two conflicting pieces of advice—and leave it to the poets to sort that out.

First, if you are interested in a project/subject—don’t be too worried in the beginning if it will give you the material for two poems or two hundred. Try it out. If it interests you, write about it. If you listen to your inner editor (no one would want to read a poem about this! I can’t write more than one poem about this!) you will not write a project book. You will not write at all!

Second, quite the opposite, pick something that really, deeply interests you (obsession!), not something the critical/editor part of your brain sees as “something that would make a good book.” If you didn’t guess already from the number of times I have used the world “obsession,” I think a project book requires a commitment beyond the rational.