Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

Book Title, Press, Year of Publication:

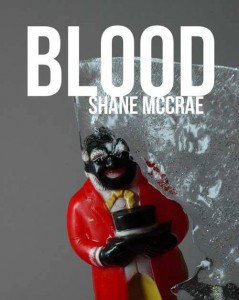

Blood, Noemi Press, 2013

Synopsis: Poems in which some of the ramifications of slavery and racism in the United States are explored.

What do you think makes your book (or any book) a “project book”?

I think intention plays a large part, and maybe that’s obvious—maybe it would be better to say, “an intention brought to a conclusion that bears some resemblance to the conclusion imagined or imaginable at the formation of the intention.” Blood started out as a book entirely about Margaret Garner, but after writing about 20 pages of Margaret Garner poems, I discovered I didn’t have any more Margaret Garner poems in me, and realized that I wanted, instead, to write poems based on slave narratives. And after writing a handful of those, I realized that the project of writing poems about Margaret Garner had instead become a project of writing poems about slavery in the United States. A project book is what happens when a writer can’t escape an idea.

Why this subject (or constraint)?

I’m not sure I know. Lately, I’ve been called upon to consider this very question in a variety of contexts, and I’ve come to realize that I might very well have chosen the subject of the book because I feel insufficiently black (and maybe I need to write a book about that). The truest–to-the-moment-of-conception answer I can give is that I felt like I couldn’t go on writing books if I didn’t write this book.

Are you comfortable with the term “project book”?

Sure! I will confess to never having used it, and possibly never having seen it used, but I think I will use it, at least when I mutter to myself, to talk about, well, project books.

How important was it for you that each poem could “stand on its own” or that the poems should rely on other poems in the book, or on the premise of the project itself, to succeed? What challenges did this present for you when writing single poems or structuring the book overall?

I’ve always worried about this issue—because, for whatever reason (anxiety, insecurity, some third thing), I’ve always wanted my poems to be “publishable” (I put that in quotes but I’m not quoting anybody, and I don’t even know what I mean by putting that in quotes—probably I mean I’m afraid to admit my own ambition), and, with publishability in mind, I’ve felt it was important that the poems be able to stand on their own. But that has often meant, with regard to sequences of poems, trying to find some way to orient the reader in each poem without sacrificing the readability of the sequence as a whole. I think this is perhaps not so difficult with a sequence dominated by a strong character or characters (see The Dream Songs), but, until I wrote the main sequence in my third book, I had never written that kind of sequence (the Margaret Garner poems, I think it would be more accurate to say, are dominated by one particular act of a strong character, rather than by the character herself). And it can be hard to orient the reader to a sequence’s particular situation, etc. in each poem without making the poems seem repetitive when read together. I’ve tried to resolve this difficulty by embracing the repetitiveness, making it a conscious formal element.

At any point did you feel you were including (or were tempted to include) weaker poems in service of the project’s overall needs? This is a risk, and a common critique, of many project books. How did you deal with this?

I have felt that a few times, yes—and I’ve tried to deal with it (and I know that by saying this I run the risk of making my projects sound too deliberate, too calculated) by writing a stronger poem that does the same work as the weak poem, and then replacing the weak poem with the stronger poem. I don’t think I could stand, in the end, leaving a poem I thought was weak in (which is not to say that all my poems in all my books are strong, but only that I, with my particular and obvious prejudices, think they’re ok).

Did you fully immerse yourself in writing this project book, or did you allow yourself to work on other things?

Yes—but only because I couldn’t really write anything else while I was working on it. Apparently, I can be a little single-minded—which is maybe a good thing for somebody who wants to write projects, sequences, and long poems!—and that has meant that I can’t let a particular subject go until I’ve exhausted my thinking about it. Luckily, given the usual quantity of my thinking, that doesn’t often take long.

Did you ever lose momentum, bore yourself, or worry that your project could not be sustained for a full-length book? How did you push through?

I lost momentum, yes, as I mentioned a few answers back, when writing the poems about Margaret Garner that make up the first section of Blood. And, in a way, I didn’t push through—instead, I panicked for a while, actually for real feeling a little scared that I had written all those poems for nothing, and then, almost by accident, discovered how I could expand the project and keep moving forward. But I had to change the project to keep the project alive—I wasn’t able to write more Margaret Garner poems.

What advice can you offer other writers, particularly emerging writers or poetry students who may be using the project book as a guiding principle for their own work?

You know, I think I might advise emerging writers and students to not use the project book as a guiding principle for their work. I’ve written three project books in a row—Blood, Forgiveness Forgiveness (which comes out in the fall of 2014), and The Animal Too Big to Kill (which comes out in the fall of 2015)—and I’m actually really looking forward to taking a break from writing that kind of book. Partially, I worry about project books because projects books speak convincingly to several of my anxieties at once: They seem major/important; and they unburden me, to a certain extent, of the need to think of something to write about (if I’m writing a book about slavery and its aftermath, I know that whatever I write will have something to do with that subject). I think artists (and I feel pretentious even obliquely referring to myself as an “artist”—I’m sorry) must be suspicious of anything that makes them feel at ease with the making of art. Go in fear of routines! And a project book IS a routine, and—in my experience, at least—a comforting one, at that. I also think emerging writers and students especially should at all times feel free to write the next poem, regardless of what the next poem might be.